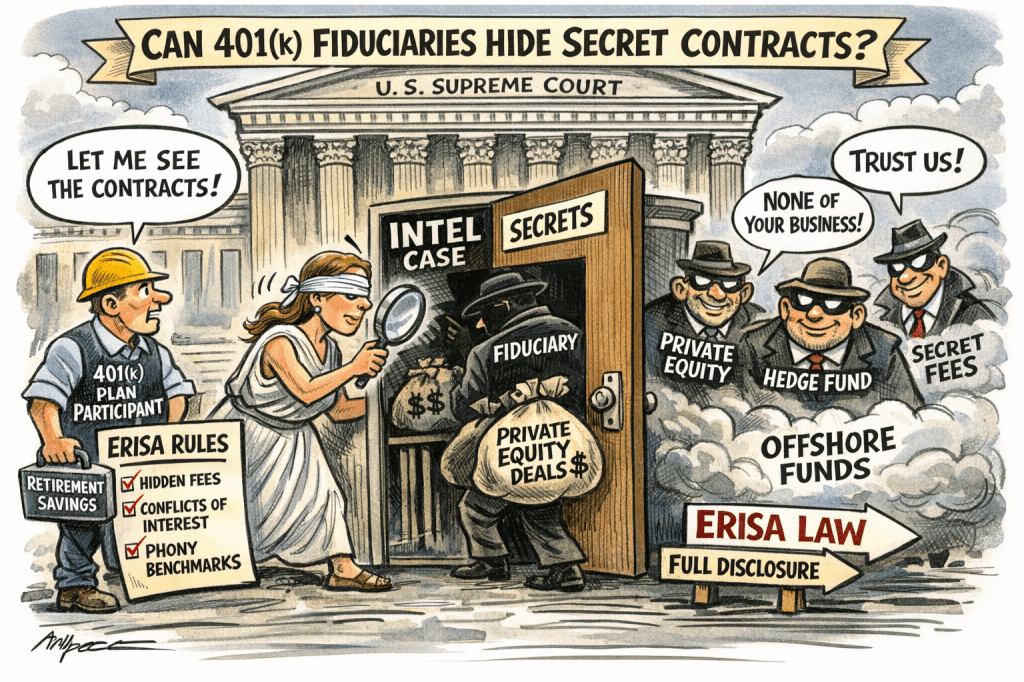

The retirement industry would like you to believe that the Supreme Court’s decision to hear Anderson v. Intel is a narrow, technical dispute about whether “alternative investments” belong in 401(k) plans.

That is industry spin.

The Intel case is not about whether private equity is “good” or “bad.”

It is about whether ERISA fiduciaries can hide the governing investment contracts, invent benchmarks, and still claim compliance with the strictest fiduciary law in the country.

If Intel prevails, the consequences will not stop with private equity.

They will extend directly to target-date funds, annuities, private credit, and any opaque product that depends on secrecy to survive scrutiny.

The Industry Narrative: “Nothing to See Here”

Industry groups such as NAPA frame Intel as reassurance:

- Private equity is just another asset class

- Fiduciaries followed a prudent process

- Plaintiffs are asking courts to micromanage investments

- Disclosure of contracts is unnecessary

This framing is designed to shift the focus away from the core problem:

Intel will not disclose the private-equity contracts—nor even the names of the funds—while asking courts to assume those contracts are prudent, fairly priced, and conflict-free.

That is not how ERISA works.

The Real Issue: You Cannot Prove Prudence While Hiding the Contract

ERISA is not a “trust us” statute.

Under ERISA §404 and §406:

- Fiduciaries must demonstrate prudence and loyalty

- Transactions with parties in interest are presumptively prohibited

- Fiduciaries—not participants—bear the burden of proving an exemption

As the Supreme Court made clear in Cunningham v. Cornell, once a prohibited transaction is plausibly alleged, the burden shifts to the fiduciary.

That burden cannot be met if the fiduciary refuses to disclose:

- The investment contract

- The fee and carry structure

- The valuation methodology

- The indemnification provisions

- The conflicts and affiliate transactions

Secrecy is not neutral.

Secrecy defeats the exemption.

Private Equity in a 401(k) Is Not a “Fund” — It’s a Contract

This is where the industry misleads courts and fiduciaries.

Private equity is not a security with a market price.

It is a bespoke service contract governed by a limited partnership agreement.

That contract determines:

- Who controls valuation (the manager)

- How performance is measured (IRR and GP-asserted NAV)

- How fees are extracted (management fees, transaction fees, carry)

- How conflicts are resolved (usually in favor of the GP)

Without seeing the contract, there is no way to benchmark, monitor, or audit the investment.

That is not a technical quibble.

It is a fatal fiduciary defect.

The Intel Case Mirrors TIAA’s Target-Date “Risk Illusion”

If this sounds familiar, it should.

Intel’s strategy—hiding private-equity contracts while claiming prudence—is functionally identical to TIAA’s target-date fund strategy of hiding annuity contracts inside CITs and separate accounts.

In both cases:

- The core economic engine is contractual, not market-based

- The risks are masked by invented benchmarks

- The valuation depends on manager discretion

- The fiduciary claims “diversification” while avoiding disclosure

As I explained in TIAA’s Target Date Funds Are Built on a Risk Illusion, you cannot create real diversification—or real performance—by hiding contractual risk behind smoothed numbers.

Private equity in a 401(k) target-date fund is simply the next iteration of the same illusion.

Fake Benchmarks Are the Common Thread

Intel’s defenders repeatedly argue that the plan used “appropriate benchmarks.”

But non-investable benchmarks are not benchmarks.

Private equity relies on:

- Lagged, GP-asserted NAVs

- IRRs that ignore cash-flow timing risk

- Peer universes built from the same flawed data

This is no different from annuity providers benchmarking opaque general-account products against invented indices that no participant could ever invest in.

ERISA does not permit fiduciaries to benchmark themselves to their own homework.

Why the Supreme Court Took the Case

The Supreme Court did not take Intel because it wants to bless private equity in 401(k)s.

It took the case because the lower courts have allowed fiduciaries to use opacity as a litigation shield, undermining ERISA’s enforcement framework.

The question before the Court is simple:

Can an ERISA fiduciary satisfy its duties while hiding the governing investment contracts from participants and courts?

If the answer is yes, ERISA’s prohibited-transaction rules collapse—not just for private equity, but for:

- Annuities

- Private credit

- Insurance separate accounts

- Crypto-linked products

- Any future opaque “innovation”

Bottom Line for Fiduciaries

This case is a warning.

If your investment strategy depends on:

- Secret contracts

- Invented benchmarks

- Smoothed valuations

- “Trust us” disclosures

you do not have an innovation problem.

You have a fiduciary problem.

The Supreme Court should—and likely will—make clear that ERISA does not permit secrecy as a substitute for prudence.

And when it does, the fallout will reach far beyond Intel.

Appendix 1 Why the “Meaningful Benchmark” Standard Is a Judicial Illusion Built for Wall Street

Over the last decade, a judicially fabricated standard has crept into ERISA litigation: the so-called “meaningful benchmark” requirement for claims alleging imprudence or excessive costs.

This appendix explains:

- Where the concept came from

- Why it is illegitimate as a substantive rule

- How it masks high-fee, high-risk products that cannot be meaningfully benchmarked

1. Origins: A Procedural Pleading Universe, Not an Investment Principle

The idea of a “meaningful benchmark” did not originate in investment theory, economics, or statutes. It was born out of ERISA procedural case law, largely as a 12(b)(6) pleading standard for plaintiffs alleging fiduciary breaches based on investment performance or fees.

The early case law adopted by some circuits required that, to survive a motion to dismiss, a complaint alleging underperformance or excessive costs must include a comparator that is sufficiently similar — an “apples-to-apples” alternative that plausibly shows the fiduciary could have done better. Courts demanded such comparators because plaintiffs often had no discovery, and judges were (purportedly) reluctant to let cases proceed on uninformed guesses about what the fiduciary could have done differently.

But critically:

- There is no statute that requires a “meaningful benchmark.”

- ERISA’s prudence standard focuses on process, not performance relative to a counterfactual benchmark.

- Benchmarks were a judicial convenience, not a substantive legal test.

2. It Is a Procedural Standard, Not a Substantive Investment Rule

The “meaningful benchmark” doctrine is a pleading rule — a device courts use to decide whether a complaint plausibly alleges imprudence before any discovery. It does not represent a real investment standard under ERISA or fiduciary law.

Indeed:

- Some courts require it at the motion-to-dismiss stage.

- Other circuits reject it as inappropriate fact-finding before discovery.

The Supreme Court now is considering this very issue in the Intel/Anderson cases — whether a meaningful benchmark is required at all at the pleading stage. The fact that this question has reached the Supreme Court underscores how unsettled and judge-crafted this standard really is.

In other words, meaningful benchmark is not a regulatory requirement; it is a judge’s attempt to police litigation before discovery by demanding early comparators. It is a procedural gatekeeper, not substantive law.

3. Why It Is Deceptive — Especially Against Insurance and Annuity Products

The meaningful benchmark standard sounds appealing — who wouldn’t want apples-to-apples comparisons? But in practice, it gives impermissibly broad cover to Wall Street, insurance companies, and institutional defenders because:

📌 a) Certain products cannot be benchmarked

· Fixed annuities

· General account insurance contracts

· Proprietary separate accounts

· Private equity and hedge funds

These products have no market-priced peers — you cannot find another open-end mutual fund that does what a fixed annuity does under discretionary crediting and balance-sheet mechanics.

Nothing in finance theory or asset pricing mandates that annuities must be compared to Vanguard, BlackRock, or S&P 500 products. Benchmarks are easier for public market instruments precisely because they have prices. Annuities do not. Thus, the meaningful benchmark standard is illogical when it comes to products that cannot be benchmarked.

4. The Standard Is Being Used to Hide, Not Reveal, Risk

The meaningful benchmark doctrine effectively says:

“If you cannot show an obvious benchmark that demonstrates harm, you have no case.”

That standard flips fiduciary law on its head.

Under ERISA, the duty of prudence is about process and risk-adjusted judgment — not about whether some benchmark existed on which the fiduciary could have hypothetically outperformed. Instead, defendants have latched on to this judicial invention to argue that a lack of benchmark equals lack of harm — a position that serves Wall Street and insurance producers very well.

5. The Investment Industry Loves It — Because It Lets Them Sneak In Opaque, High-Fee Products

Investment intermediaries and insurers have a strategic advantage when the standard is “meaningful benchmark.”

Why?

Because the industry sells products that do not have logical benchmarks:

- Annuities

- Indexed insurance contracts

- Private market funds

- Multi-asset strategies with proprietary glidepaths

These products cannot be meaningfully compared to:

- Public index funds

- Mutual funds

- Standard benchmarks

So the industry says:

“There is no market benchmark — therefore the allegation fails.”

This argument presumes the answer, rather than evaluating whether the fiduciary followed a prudent process or whether the product’s risks and costs were adequately disclosed and managed.

6. The Standard Was Never Explained in Investment Texts or Statutes

You won’t find “meaningful benchmark” defined in:

- ERISA itself

- DOL regulations

- Investment management texts

- SEC rules

It is purely a judicial procedural rule, created in cases like Ruilova, Barrick Gold, Oshkosh, and others that required comparators in pleadings. But there is no canonical source where the concept was explained and justified in investment academic literature. It is a creature of litigation economics, not fiduciary economics.

Now the Supreme Court is being asked to decide whether that procedural invention should even survive constitutional and statutory scrutiny.

7. The Standard Shields Wall Street at the Cost of Participants

Here’s the real impact:

👉 Judges who require a “meaningful benchmark” are effectively saying to plaintiffs:

“If you can’t find a near-identical investment strategy with public pricing, you have no case.”

This approach:

- Promotes a hindsight performance regime

- Undermines process-based prudence

- Shields producers of opaque, illiquid, proprietary products

- Raises barriers to scrutiny even where conflicts and undisclosed compensation are obvious

That is the opposite of ERISA’s purpose.

ERISA is supposed to protect participants from conflicts of interest, hidden costs, and imprudent choices, not protect Wall Street by enforcing a “benchmark inoculation” against scrutiny.

8. Because Judges Lack Investment Economics Training, They Default to Benchmarks

One reason the meaningful benchmark standard took hold is that many judges:

- Lack finance or investment economics training

- Are uncomfortable evaluating risk and compensation structures that do not fit classic mutual fund models

- Are influenced by industry amici and defense briefings that frame benchmarks as the only way to demonstrate imprudence

The result:

A “benchmark requirement” becomes a judicial shortcut — not because it is technically correct, but because it makes litigation easier for courts that do not want to engage with real economics.

This dynamic benefits Wall Street, not participants.

9. As We Explained Earlier in Commonsense, Benchmarks Don’t Work for Complex Solutions

Our earlier discussion of target-date benchmarks — including why simple index comparisons are inadequate and how product design matters more than benchmarking — already exposed this fallacy. Benchmarks assume liquidity, transparency, and comparability — all of which are absent in the annuity, separate account, and private market contexts at issue in Intel, Cho, and other cases.

10. Bottom Line — “Meaningful Benchmark” Is a Procedural Illusion

The “meaningful benchmark” standard is not a substantive fiduciary rule; it is:

- A judicial pleading device

- A procedural barrier

- A way for judges uncomfortable with investment economics to avoid deep analysis

- A shield for the industry to hide products that cannot be bench-marked

And it should not be used to legitimize high-fee, high-risk contracts in ERISA plans — especially when:

- The products are opaque;

- Compensation is hidden;

- Benchmarks don’t exist; and

- Participants rely on fiduciaries, not benchmarks, for informed decisions.

Appendix 2 — Lessons from Pizarro v. Home Depot for the Intel Litigation

Recent commentary by James W. Watkins, III, JD, CFP® on the Pizarro v. Home Depot litigation — especially his critiques of the EBSA amicus briefs in that case — highlights fiduciary failures and regulatory capture dynamics that are deeply relevant to the Intel / Anderson litigation now before the Supreme Court.(fiduciaryinvestsense.com; fiduciaryinvestsense.com)

Watkins’s insights reveal systemic issues in how fiduciary standards are being interpreted and enforced — or, more accurately, how they are being diluted by regulators, industry amici, and courts. As Intel asks whether courts can demand “meaningful benchmarks” at the pleading stage, Watkins’s Home Depot critique shows why that question cannot be abstracted from larger issues of disclosure, economic substance, and fiduciary candor.

1. Disclosure and Secrecy: The Core of Fiduciary Duty

One of Watkins’s central points in Fair Dinkum: A Critique of the EBSA’s Amicus Brief in Pizarro v. Home Depot is that the Department of Labor (via EBSA) abandoned core fiduciary responsibilities by advocating positions that underplay the importance of disclosure and economic substance.

Specifically:

- EBSA’s amicus brief emphasized process compliance over economic substance, effectively arguing that plan sponsors who followed certain procedural boxes were insulated from liability — even if they failed to disclose material economic facts about the investments at issue.

- This mirrors the antinomian argument we see in Intel/Anderson: that plaintiffs must plead a “meaningful benchmark” before discovery — a procedural hurdle that distracts from whether the fiduciary failed to disclose material investment risks and economic realities in the first place.

Watkins’s critique of the EBSA amicus brief demonstrates a consistent pattern: regulators preferring formalism over substance, process over transparency.

In Intel, this manifests as judicial and amicus rhetoric that treats benchmarks as a proxy for prudence instead of focusing on whether fiduciaries provided investors with material information needed to evaluate risk and compensation.

2. Fiduciary Loyalty vs. Regulatory Theater

In The DOL’s Pizarro v. Home Depot Amicus Brief: Borzi and Gomez Don’t Live Here Anymore, Watkins documents how EBSA’s position effectively reframes fiduciary law to insulate conflict-laden decisions so long as process step boxes are checked.

The essential critique:

- Fiduciary law historically requires both prudent process and loyalty to act solely in the interest of participants.

- EBSA’s brief prioritized procedural immunities, not fiduciary loyalty — downplaying whether plan sponsors adequately disclosed economic conflicts.

This insight directly applies to Intel/Anderson. The push for a “meaningful benchmark” at the motion-to-dismiss stage:

- Empowers defendants to argue that as long as there is no obvious comparator, there is no plausible claim — even if fiduciaries concealed material risk, compensation, or conflicts.

- Shifts the focus from fiduciary loyalty and investor protection to procedural immunity.

Watkins’s work shows why this shift is perilous: it validates the very illusions that erode fiduciary protections — the same illusions central to the Intel and Cho litigation context.

3. Proprietary Economics and the Failure of Transparency

A common theme in Watkins’s writing on Home Depot is the danger of proprietary or undisclosed economics — where fiduciaries or issuers refuse to provide meaningful economic information.

In the Home Depot context, the EBSA amicus brief was criticized for diminishing the value of transparency:

The brief implied that plan sponsors can satisfy ERISA so long as they rely on procedural checklists and industry standards — even when economic substance and proprietary fee structures are opaque to participants and fiduciaries alike.

This has direct parallels to the Intel case’s context:

- Many of the allegedly imprudent decisions at issue involved products (annuities, proprietary CITs, etc.) with undisclosed compensation via spread, discretionary pricing, and other opaque features.

- A benchmark requirement effectively punishes plaintiffs for not discovering and pleading economic comparators that only discovery will reveal — a barrier rooted in secrecy, not sound fiduciary analysis.

Watkins’s critique highlights the inconsistency in accepting opaque proprietary economics as part of a safe process — which dovetails with Intel’s concern about how courts treat benchmarks without probing the underlying economics.

4. Regulatory Capture and the Fiduciary Standard’s Erosion

Watkins’s commentary repeatedly underscores a broader institutional issue: regulatory capture, where the very agencies tasked with protecting workers tilt too heavily toward industry risk minimization.

In The DOL’s Pizarro v. Home Depot Amicus Brief…, he observes that:

Regulators have shifted toward interpretations that emphasize procedural compliance over fiduciary duty grounded in economic substance, transparency, and loyalty to participants, a pattern that disadvantages claimants and advantages industry defenders.

This regulatory shift mirrors judicial trends that:

- Require plaintiffs to overcome stringent procedural banners (like meaningful benchmarks);

- Allow defendants to hide behind process boxes;

- Tolerate industry amici positions that diminish the core fiduciary obligations.

In the Intel litigation, this context matters because the Supreme Court’s treatment of pleading standards can either reinforce or reverse this trend. If courts continue to elevate procedural hurdles (like benchmarks) above substantive inquiry into transparency, risk, and conflicts, the regulatory erosion Watkins describes will be cemented in doctrine.

5. What Judges and Amici Miss When They Focus on Benchmarks

From Watkins’s Home Depot insights, three interlocking lessons emerge that should inform how we read Intel:

A. Benchmarks Are Not a Substitute for Disclosure or Loyalty:

Benchmarks are tools for analysis — but they do not deliver material information to participants nor do they safeguard against conflicted economics.

B. Procedural Immunities Cannot Cure Conflicted Economics:

Neither a checklist of steps nor an absence of a meaningful benchmark at the pleadings stage can justify a decision where economic risks and conflicts were not disclosed.

C. Regulatory and Judicial Emphasis on Procedural Thresholds Encourages Secrecy:

When regulators and courts raise procedural bars (e.g., benchmarks before discovery), they inadvertently incentivize opacity, not fiduciary candor.

Watkins’s critiques show that fiduciary duty is both procedural and substantive — it demands transparency and duty of loyalty, not just procedural boxes.

6. Implications for Intel’s Outcome and Fiduciary Law

Taken together, Watkins’s writings on Home Depot illuminate three key takeaways relevant to the Supreme Court’s consideration of benchmarks in Intel/Anderson:

- Benchmarks cannot be elevated to a doctrinal requirement that displaces core fiduciary obligations — especially where proprietary economics and conflicts are in play.

- Judicial or regulatory moves toward proceduralism (benchmarks before discovery) embed the same kind of fiduciary illusions that Intel criticizes — secrecy, veneer of process, and reliance on industry dicta.

- A correct fiduciary analysis must center economic substance, transparency, and conflict disclosure — not shortcut substitutes like early benchmarks.

In other words, Intel should be read as an opportunity to reaffirm fiduciary law’s core values, not to entrench a pleading-stage benchmark regime that rewards secrecy and shields conflicted conduct — the very trends Watkins has decried in Pizarro.