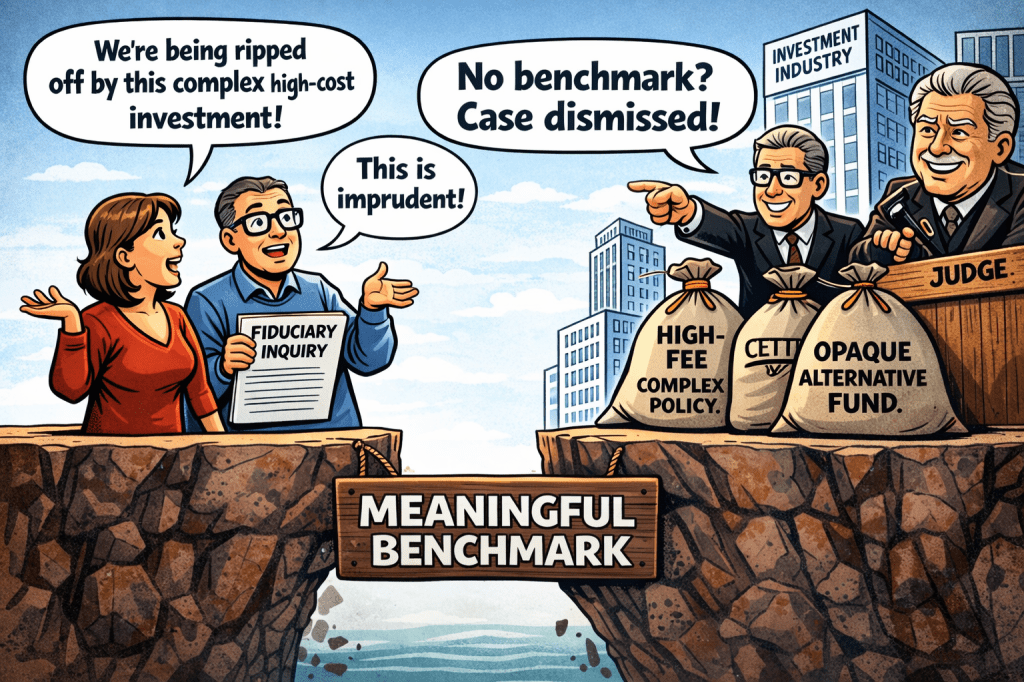

Over the last decade, a judicially fabricated standard has crept into ERISA litigation: the so-called “meaningful benchmark” requirement for claims alleging imprudence or excessive costs.

This appendix explains:

- Where the concept came from

- Why it is illegitimate as a substantive rule

- How it masks high-fee, high-risk products that cannot be meaningfully benchmarked

1. Origins: A Procedural Pleading Universe, Not an Investment Principle

The idea of a “meaningful benchmark” did not originate in investment theory, economics, or statutes. It was born out of ERISA procedural case law, largely as a 12(b)(6) pleading standard for plaintiffs alleging fiduciary breaches based on investment performance or fees.

The early case law adopted by some circuits required that, to survive a motion to dismiss, a complaint alleging underperformance or excessive costs must include a comparator that is sufficiently similar — an “apples-to-apples” alternative that plausibly shows the fiduciary could have done better. Courts demanded such comparators because plaintiffs often had no discovery, and judges were (purportedly) reluctant to let cases proceed on uninformed guesses about what the fiduciary could have done differently.

But critically:

- There is no statute that requires a “meaningful benchmark.”

- ERISA’s prudence standard focuses on process, not performance relative to a counterfactual benchmark.

- Benchmarks were a judicial convenience, not a substantive legal test.

2. It Is a Procedural Standard, Not a Substantive Investment Rule

The “meaningful benchmark” doctrine is a pleading rule — a device courts use to decide whether a complaint plausibly alleges imprudence before any discovery. It does not represent a real investment standard under ERISA or fiduciary law.

Indeed:

- Some courts require it at the motion-to-dismiss stage.

- Other circuits reject it as inappropriate fact-finding before discovery.

The Supreme Court now is considering this very issue in the Intel/Anderson cases — whether a meaningful benchmark is required at all at the pleading stage. The fact that this question has reached the Supreme Court underscores how unsettled and judge-crafted this standard really is.

In other words, meaningful benchmark is not a regulatory requirement; it is a judge’s attempt to police litigation before discovery by demanding early comparators. It is a procedural gatekeeper, not substantive law.

3. Why It Is Deceptive — Especially Against Insurance and Annuity Products

The meaningful benchmark standard sounds appealing — who wouldn’t want apples-to-apples comparisons? But in practice, it gives impermissibly broad cover to Wall Street, insurance companies, and institutional defenders because:

📌 a) Certain products cannot be benchmarked

· Fixed annuities

· General account insurance contracts

· Proprietary separate accounts

· Private equity and hedge funds

These products have no market-priced peers — you cannot find another open-end mutual fund that does what a fixed annuity does under discretionary crediting and balance-sheet mechanics.

Nothing in finance theory or asset pricing mandates that annuities must be compared to Vanguard, BlackRock, or S&P 500 products. Benchmarks are easier for public market instruments precisely because they have prices. Annuities do not. Thus, the meaningful benchmark standard is illogical when it comes to products that cannot be benchmarked.

4. The Standard Is Being Used to Hide, Not Reveal, Risk

The meaningful benchmark doctrine effectively says:

“If you cannot show an obvious benchmark that demonstrates harm, you have no case.”

That standard flips fiduciary law on its head.

Under ERISA, the duty of prudence is about process and risk-adjusted judgment — not about whether some benchmark existed on which the fiduciary could have hypothetically outperformed. Instead, defendants have latched on to this judicial invention to argue that a lack of benchmark equals lack of harm — a position that serves Wall Street and insurance producers very well.

5. The Investment Industry Loves It — Because It Lets Them Sneak In Opaque, High-Fee Products

Investment intermediaries and insurers have a strategic advantage when the standard is “meaningful benchmark.”

Why?

Because the industry sells products that do not have logical benchmarks:

- Annuities

- Indexed insurance contracts

- Private market funds

- Multi-asset strategies with proprietary glidepaths

These products cannot be meaningfully compared to:

- Public index funds

- Mutual funds

- Standard benchmarks

So the industry says:

“There is no market benchmark — therefore the allegation fails.”

This argument presumes the answer, rather than evaluating whether the fiduciary followed a prudent process or whether the product’s risks and costs were adequately disclosed and managed.

6. The Standard Was Never Explained in Investment Texts or Statutes

You won’t find “meaningful benchmark” defined in:

- ERISA itself

- DOL regulations

- Investment management texts

- SEC rules

It is purely a judicial procedural rule, created in cases like Ruilova, Barrick Gold, Oshkosh, and others that required comparators in pleadings. But there is no canonical source where the concept was explained and justified in investment academic literature. It is a creature of litigation economics, not fiduciary economics.

Now the Supreme Court is being asked to decide whether that procedural invention should even survive constitutional and statutory scrutiny.

7. The Standard Shields Wall Street at the Cost of Participants

Here’s the real impact:

👉 Judges who require a “meaningful benchmark” are effectively saying to plaintiffs:

“If you can’t find a near-identical investment strategy with public pricing, you have no case.”

This approach:

- Promotes a hindsight performance regime

- Undermines process-based prudence

- Shields producers of opaque, illiquid, proprietary products

- Raises barriers to scrutiny even where conflicts and undisclosed compensation are obvious

That is the opposite of ERISA’s purpose.

ERISA is supposed to protect participants from conflicts of interest, hidden costs, and imprudent choices, not protect Wall Street by enforcing a “benchmark inoculation” against scrutiny.

8. Because Judges Lack Investment Economics Training, They Default to Benchmarks

One reason the meaningful benchmark standard took hold is that many judges:

- Lack finance or investment economics training

- Are uncomfortable evaluating risk and compensation structures that do not fit classic mutual fund models

- Are influenced by industry amici and defense briefings that frame benchmarks as the only way to demonstrate imprudence

The result:

A “benchmark requirement” becomes a judicial shortcut — not because it is technically correct, but because it makes litigation easier for courts that do not want to engage with real economics.

This dynamic benefits Wall Street, not participants.

9. As We Explained Earlier in Commonsense, Benchmarks Don’t Work for Complex Solutions

Our earlier discussion of target-date benchmarks — including why simple index comparisons are inadequate and how product design matters more than benchmarking — already exposed this fallacy. Benchmarks assume liquidity, transparency, and comparability — all of which are absent in the annuity, separate account, and private market contexts at issue in Intel, Cho, and other cases.

10. Bottom Line — “Meaningful Benchmark” Is a Procedural Illusion

The “meaningful benchmark” standard is not a substantive fiduciary rule; it is:

- A judicial pleading device

- A procedural barrier

- A way for judges uncomfortable with investment economics to avoid deep analysis

- A shield for the industry to hide products that cannot be bench-marked

And it should not be used to legitimize high-fee, high-risk contracts in ERISA plans — especially when:

- The products are opaque;

- Compensation is hidden;

- Benchmarks don’t exist; and

- Participants rely on fiduciaries, not benchmarks, for informed decisions.

https://commonsense401kproject.com/2026/01/17/the-supreme-courts-intel-case-is-about-secrecy-fake-benchmarks-and-fiduciary-illusions/ https://commonsense401kproject.com/2025/07/09/target-date-benchmarks-chatgpt/

Appendix — Why “Meaningful Benchmarks” Fail in the Real Investment World of 401(k)s

This appendix ties together three threads I have been documenting for years:

- Courts are demanding a “meaningful benchmark” at the pleading stage,

- The reality that many 401(k) structures don’t have true benchmarks (annuities, opaque CIT sleeves),

- And the deeper truth that even where benchmarks exist (target dates, active mutual funds), benchmarking is easily gamed because asset allocation dominates outcomes.

The result? A legal standard built on a market myth.

1) What fiduciaries can actually control

As your benchmarking chapter reminds us:

The dominant driver in performance that fiduciaries control is fees. Asset allocation is largely chosen by participants. Ch13MFPerfBenchmarksFeesSep24

That’s not rhetoric. That’s supported by:

- SPIVA scorecards (active underperformance),

- Pew/Yale/SEC/DOL research on fee drag,

- And decades of academic work showing that fees are the only guaranteed negative in investment performance.

So when courts ask plaintiffs to produce a “meaningful benchmark,” they are asking the wrong question.

The right fiduciary question is:

Did the fiduciary select a structure where fees and performance are measurable and comparable at all?

2) SEC mutual funds: why benchmarking works here

SEC-registered mutual funds are the gold standard because they provide:

- Daily NAV (mark-to-market),

- Transparent expense ratios,

- Prospectus/SAI disclosures,

- Comparable peer data,

- Long performance histories,

- GIPS-like discipline embedded by regulation.

This is why tools like AMVR (Watkins) work.

This is why Brotherston endorsed index comparisons.

This is why index funds reduce fiduciary risk.

Because true benchmarking is possible.

3) CITs, annuities, and private sleeves: where benchmarking collapses

Your chapter makes this explicit:

- Many CITs do not disclose underlying holdings or fees.

- General Account and Separate Account annuities use book value, not market value.

- Private equity, private credit, and real estate funds often do not comply with GIPS.

- The only observable number is the crediting rate.

There is no traditional benchmark. Only comparables. Ch13MFPerfBenchmarksFeesSep24

That’s a crucial distinction courts are missing.

You cannot benchmark something that refuses to be benchmarked.

You can only compare:

- TIAA crediting rate vs. Principal crediting rate,

- Stable value crediting vs. Hueler median,

- GA annuity vs. synthetic stable value vs. G Fund.

Those are comparables, not benchmarks.

Yet courts are demanding a “benchmark” where none can exist.

4) Stable value proves the point

The industry itself admits this problem.

As documented:

- 23 of 35 managers benchmark to money markets (which they always beat),

- Others use CMT, GIC index, Hueler, SIMI, blended bond indices,

- Consultants admit book value is meaningless for manager evaluation,

- Market value returns are hidden by smoothing,

- GIPS excludes GICs from mark-to-market.

The industry can’t agree on a benchmark because there isn’t one.

Yet courts expect plaintiffs to produce one at the pleading stage.

5) Target date funds: even transparency doesn’t save benchmarking

Even when you do have SEC transparency (mutual fund TDFs), benchmarking still breaks down.

Why?

Because 90% of TDF performance is asset allocation.

A manager can:

- Shift glidepath equity by 5–10%,

- Time international vs domestic,

- Adjust bond duration,

- Change risk posture,

…and instantly make any index comparison meaningless.

That’s why you wrote:

TDF benchmarks can be manipulated by market timing, making them useless.

So if benchmarking is this fragile even in transparent mutual funds, imagine how absurd it is to demand it for:

- CIT target dates with private sleeves,

- Insurance-wrapped target dates,

- Annuity-backed capital preservation.

6) The legal fiction exposed

Courts now say:

“Show me a meaningful apples-to-apples benchmark or your case fails.”

But in large parts of the 401(k) world:

- Apples are hidden,

- Oranges are opaque,

- And the fiduciary chose the fruit bowl.

The inability to benchmark is not a plaintiff failure.

It is evidence of a fiduciary failure to select transparent, measurable investments.

7) What the CFA and GIPS standards quietly say

Your chapter cites the CFA Primer:

Fiduciaries should require:

- Clear benchmarks

- Transparent holdings

- Defined risk/return objectives

- Reporting standards

Many annuity managers, CIT structures, and private vehicles cannot comply.

That’s the tell.

If it can’t be benchmarked under CFA/GIPS ideals, it shouldn’t be in a 401(k).

8) Why index funds dominate large plans

SPIVA shows 85–91% of active managers lose to their benchmark over 10 years.

Vanguard’s own data: 0 of 87 active funds beat benchmarks meaningfully.

Why do mega-plans go index?

Because benchmarking is easy and defensible.

That’s fiduciary risk reduction.

9) The inversion courts are creating

Courts are turning this logic upside down:

| Investment reality | Judicial expectation |

|---|---|

| Some products cannot be benchmarked | Plaintiffs must benchmark them |

| Opaque structures hide fees/performance | Plaintiffs must prove what’s hidden |

| Comparables are the only tool | Courts demand benchmarks |

| Transparency is fiduciary duty | Opacity becomes litigation shield |

That’s backwards.

10) The Brotherston principle courts are forgetting

Brotherston said:

Compare to index funds or suitable benchmarks, and the burden shifts to fiduciaries.

Courts now require plaintiffs to do that before discovery — even when the structure prevents it.

The punchline

“Meaningful benchmark” is a judicial illusion because:

- In mutual funds, benchmarking works but is unnecessary because fees tell the story.

- In TDFs, benchmarking is manipulable because asset allocation dominates.

- In CITs, annuities, and private sleeves, benchmarking is impossible because transparency is absent.

So when courts demand benchmarks, they are demanding something the fiduciary structure itself prevents.

That’s not a pleading failure.

That’s the evidence of the fiduciary breach.

Pingback: 401(k) Disclosures – Trump DOL moving toward blocking Transparency | The CommonSense 401k Project