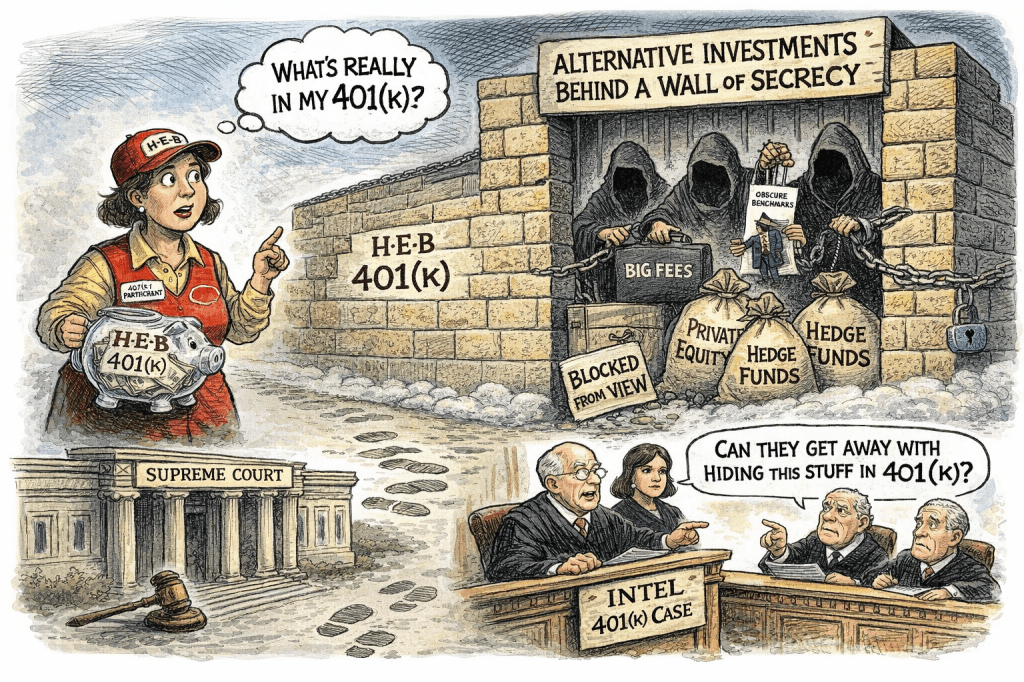

When a Plan’s Alternatives Echo the Same Secrecy and Conflicts Now Before the Supreme Court

The New York Times recently published a sympathetic profile about one H-E-B employee’s retirement savings, celebrating the virtues of long-term compounding and disciplined contributions. It’s a feel-good human narrative — but it carefully avoids the structural questions that truly matter to millions of participants.

https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/11/business/401k-heb-eryn-schultz-personal-finances.html a version outside the paywall is at https://dnyuz.com/2026/01/11/how-a-puzzling-401k-plan-changed-one-womans-life/

Let’s cut through the noise.

The Hard Numbers: H-E-B’s 401(k) Is Sitting on $330+ Million of Alternatives

If you look at H-E-B’s 2024 Form 5500 — not the glossy participant site but the actual audited schedules — you find:

- Limited partnerships (private equity): $481,112,684

- Other alternate investments (hedge funds, private credit, opportunistic funds): $128,585,560

This is over $609 million in private and alternative assets — a striking allocation in what is supposed to be a daily-valued 401(k) designed for retail savers. Even holding a conservative interpretation of categories, the plan still lists well over $300 million in hard-to-value, illiquid positions.

HEB

That kind of exposure isn’t a minor footnote. It’s a strategic investment decision with big consequences.

Stale Valuations and “Daily Liquidity” — A Problem Wrapped in Language

H-E-B discloses in its 5500 that these alternative positions are:

- Valued using “good faith estimates.”

- Using manager valuations that may lag by 4–15 weeks

- Used to price daily participant transactions

- Participants assume the risk that true values may differ materially when actual trades settle later

HEB

Translated: the plan’s “daily valuation” window is an illusion. The values that participants see when they rebalance or change allocations, can be stale, and updated only after the fact — meaning participants make real decisions based on outdated information.

This too closely resembles the valuation and benchmark games at issue in the Intel Supreme Court case — where opaque pricing, bespoke benchmarks, and frozen valuations shield fiduciaries from accountability.

Private Equity in a 401(k)? Yes — But the Problem Is Bigger Than ‘Illiquidity’

Private equity (“PE”) isn’t illegal in 401(k) plans per se. But as argued in my Commonsense401kProject.com piece, PE exacerbates core ERISA concerns around conflicts, valuation opacity, and compensation structures: https://commonsense401kproject.com/2025/10/27/private-equity-as-an-erisa-prohibited-transaction/

1) Soft-Dollar and Hidden Compensation

Many PE vehicles embed fees and compensation that don’t become transparent until years later — carried interest that accrues in ways participants don’t see, placement agent fees shared with plan service providers, and revenue sharing that goes unseen. The plan’s total recordkeeping cost picture becomes distorted.

These hidden economic interests resemble the sort of related-party and soft-dollar conflicts that ERISA’s prohibited transaction rules were designed to prevent.

2) Manager-Controlled Valuation + Lack of Objective Benchmark

PE and other alternative asset managers often control monthly or quarterly NAV establishment. That’s fine for an endowment — not fine when:

- A participant’s daily balance changes based on stale data

- Benchmarks are proprietary or ill-defined

- Participants cannot evaluate performance reasonably

ERISA’s prudence and disclosure duties assume auditable, observable benchmarks and valuations — things private markets resist.

3) Liquidity Mismatch

Daily-tradable 401(k) interests priced on stale alternative valuations simply don’t behave like truly liquid vehicles. When participants rebalance, they get a price that may not reflect actual realized market value — transferring valuation risk to participants without their informed consent.

The Supreme Court Intel Case Isn’t About Pleading Rules — It’s About Secrecy

The conventional reporting treats the Intel case as a narrow statute-of-limitations fight. That’s the superficial framing.

What’s really at stake is:

- Do fiduciaries have to disclose compensation, conflicts, and valuation mechanics transparently?

- Or can they bury this information in opaque structures, stale assumptions, and “trust us” language?

- Can participants ever compare plan performance to meaningful benchmarks — or does the “fiduciary illusion” shield fiduciary failures?

The same structural defense that shields H-E-B’s alternative allocation — “it’s complicated, trust us, these valuations are estimates, and we reserve the right to adjust later” — is the defense being tested in Intel. https://commonsense401kproject.com/2026/01/17/the-supreme-courts-intel-case-is-about-secrecy-fake-benchmarks-and-fiduciary-illusions/

The Real Questions the NYT Should Have Asked

Not:

“How did this one woman save?”

But:

- Why is a large plan diverting hundreds of millions into assets participants cannot evaluate?

- Why are valuations lagged by weeks in a daily liquidity vehicle?

- What benchmarks exist against which participants can measure performance?

- What hidden compensation flows to advisers tied to these alternative allocations?

- Is this consistent with ERISA’s core duties of loyalty, prudence, and disclosure?

These aren’t abstract academic questions. They go to the heart of whether retirement plans serve participants or structural economic interests tied to private markets and product fees.

The Convergence: H-E-B and Intel

If the Supreme Court allows fiduciaries to hide behind complexity and stale valuation benchmarks, then:

- H-E-B’s allocation structure becomes a safer defensive line

- More plans will emulate similar private market exposure without meaningful transparency

- Participants will have no clear benchmark or valuation certainty for key portions of their retirement wealth

But if the Court affirms:

- Meaningful disclosure duties

- Real benchmarks (not proprietary or opaque targets)

- A requirement that valuations reflect current participant realities

Then H-E-B’s structures — and those of countless other plans — are suddenly exposed to real fiduciary scrutiny.

The Bottom Line

Counting retirement balances is easy.

Understanding what participants own, at what price, and with what conflicts is hard.

That is the structural issue the NY Times missed — and the Supreme Court must confront.