Modern 401(k) Plans and Public Pensions Are Violating Rules Written 300 Years Ago

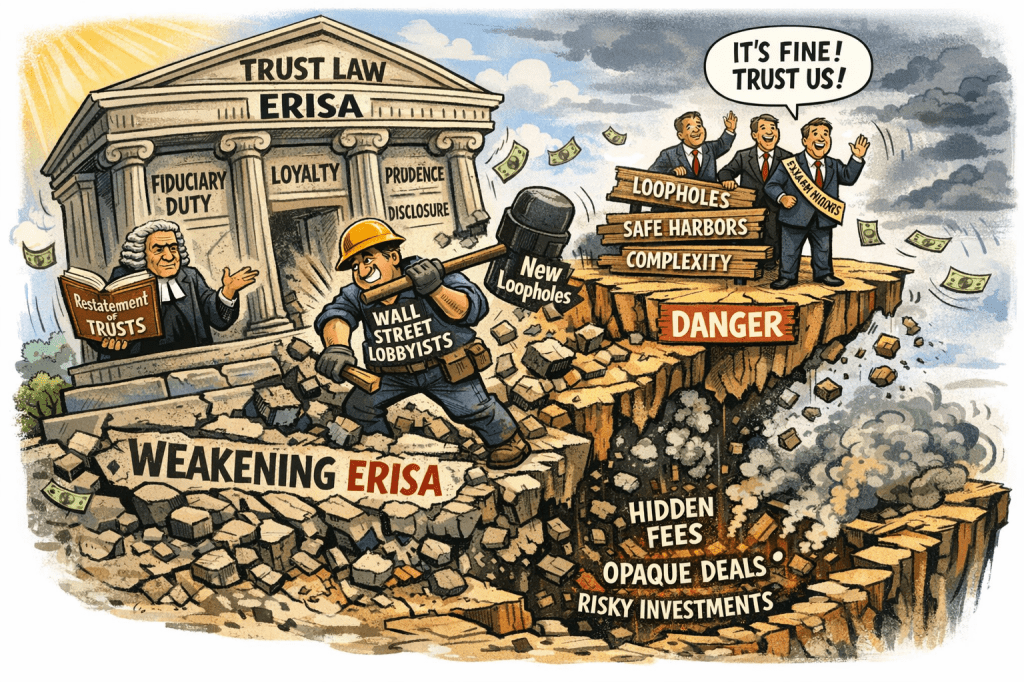

When Congress passed Employee Retirement Income Security Act in 1974, it did not invent fiduciary duty.

It imported it. Many State Fiduciary laws claim to be similar to ERISA.

The intellectual backbone of ERISA is not a securities statute. It is not an accounting rule. It is not a pension innovation.

It is the law of trusts — as summarized in the Restatement (Second) of Trusts.

That matters, because trust law is old. Very old. And very clear.

What a trustee is allowed to do (and not do)

For centuries, courts imposed simple rules on trustees:

- Duty of Loyalty — the trustee may not benefit himself, directly or indirectly.

- Duty of Prudence — the trustee must invest as a careful person would with his own money.

- Duty of Impartiality — treat beneficiaries fairly.

- Duty to Inform — beneficiaries are entitled to know what is being done with their property.

- Duty to Avoid Conflicts — even the appearance of self-dealing is forbidden.

These rules were codified and clarified in the Restatement by the American Law Institute.

Then Congress lifted them into ERISA.

ERISA is trust law applied to pensions

The people who wrote ERISA — Jacob Javits, Ted Kennedy, and others — were responding to pension looting like the Studebaker-Packard collapse.

Their solution was simple:

Treat pension managers like trustees.

That’s why ERISA uses phrases like:

- “solely in the interest of participants”

- “exclusive purpose”

- “prudence”

- “party in interest”

- “prohibited transaction”

Those are trust law phrases, not finance phrases.

The SEC laws did the same thing for retail investors

The Investment Company Act of 1940 did for mutual funds what ERISA did for pensions:

It forced:

- Daily pricing

- Fee transparency

- Independent oversight

- Restrictions on affiliated transactions

Why? Because 1920s investment trusts were abusing investors using the same tricks we see today in private markets.

Now look at many 401(k)s and other Public and Private Pensions

Ask a simple trust-law question:

If a trustee invested a widow’s trust in a vehicle where:

- Fees were hidden,

- Pricing was stale for weeks,

- Managers set their own valuations,

- Contracts were secret,

- And advisers were paid for steering money there,

would a court say that trustee met the duty of loyalty and prudence?

Of course not.

But that is exactly how modern pension and 401(k) alternative structures operate.

The great workaround of the last 30 years

Private equity, hedge funds, CITs, annuities, and “separate accounts” were all engineered to sit:

- Outside the Investment Company Act (SEC registered funds)

- In gray zones of ERISA disclosure

- Behind NDAs and proprietary claims

- Beyond meaningful benchmarking

- Under poor state regulation, outside federal regulation ie annuities and CITs

They are, functionally, pre-1940 investment trusts wearing modern legal costumes.

And they would fail a basic trust-law exam.

They are about a system that would make an 18th-century English chancery judge say:

“This trustee is hiding the books from the beneficiary.”

Which was the one thing trust law never allowed.

The irony

We didn’t need new laws to prevent this.

We wrote them in:

- 1940 (Investment Company Act)

- 1974 (ERISA)

Both based on trust law principles hundreds of years old.

The problem is not the absence of law.

The problem is that modern finance learned how to engineer around the spirit of those laws while technically staying inside the words.

The architects of U.S. investment law would look at:

- Private equity in 401(k)s https://commonsense401kproject.com/2026/01/17/the-supreme-courts-intel-case-is-about-secrecy-fake-benchmarks-and-fiduciary-illusions/

- Opaque annuities https://commonsense401kproject.com/2025/11/01/annuities-are-a-prohibited-transaction-dol-exemptions-do-not-work/ https://commonsense401kproject.com/2025/11/22/annuities-the-erisa-regulatory-hole-no-one-wants-to-talk-about/

- CIT secrecy https://commonsense401kproject.com/2025/12/07/wall-street-journal-exposes-target-date-cit-corruption-but-theyve-only-scratched-the-surface

- Crypto

And say “We already outlawed this in 1940 and 1974. How did it come back?”

The question courts and regulators should be asking

Not:

“Is this permitted by the plan document?”

But:

“Would this be permitted if this were a private trust and the beneficiary demanded the books?”

That is the fiduciary test ERISA was built on.

And it’s the test many modern retirement structures cannot pass.

Appendix: The Quiet Erosion of Trust Law Inside ERISA

The story above makes a simple point: ERISA is trust law applied to pensions.

Its backbone is the Restatement (Second) of Trusts. Its cousins are the disclosure regimes of the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and the structural protections of the Investment Company Act of 1940. Congress imported those principles into the Employee Retirement Income Security Act after pension looting scandals.

This appendix addresses a harder claim:

Over time—and especially in recent years—new rules, exemptions, and litigation trends have weakened ERISA’s trust-law core, not by repealing it, but by engineering around it.

How erosion happens (without saying “weaken ERISA”)

Modern changes rarely say, “reduce fiduciary duty.” Instead, they:

- Redefine what counts as adequate disclosure

Long documents, layered structures, and “proprietary” claims substitute for clarity. Participants receive information, but not usable information. - Expand what can be treated as ‘prudently justified’

Illiquid, opaque, hard-to-benchmark assets are normalized inside daily-valued plans so long as a paper process exists. - Rely on exemptions and safe harbors

Prohibited-transaction exemptions, rollover rules, and advice frameworks create compliance paths that dilute the bright lines trust law once enforced. - Narrow who can sue and when

Litigation doctrines and standing rules reduce the practical ability of beneficiaries to challenge conflicted structures, even when trust-law principles would condemn them. - Shift oversight from structure to documentation

If the file shows a process, courts increasingly defer—even when the underlying structure obscures fees, conflicts, or valuation risk.

The pattern across administrations (and visible now)

This trend did not begin with any single administration. But the current legislative and regulatory push—often framed around ESG, choice, or access to private markets—accelerates the shift from trust principles to paper compliance.

For example, proposals emphasizing “pecuniary factors only” or expanding access to private assets in retirement plans may sound participant-protective. In practice, without parallel requirements for fee transparency, independent valuation, and real benchmarking, they risk:

- Making it easier to justify opaque alternatives on a “financial” rationale

- Hardening the legal defense that complexity equals prudence

- Further distancing ERISA practice from the Restatement’s simple tests: loyalty, prudence, disclosure, and conflict avoidance

What trust law would still ask

A chancery judge applying trust law would ask:

- Can the beneficiary see the fees?

- Can the beneficiary verify the value?

- Can the beneficiary compare the investment to a known benchmark?

- Is anyone in the chain paid more if this option is chosen?

If the answer to any of those is “no” or “we can’t disclose,” trust law’s presumption is against the trustee.

Modern ERISA practice too often presumes the opposite: if it’s disclosed somewhere and documented, it is presumed acceptable.

Why this matters for today’s reforms

When new laws or rules are proposed—whatever their stated political goal—the test should be:

Do they move ERISA closer to or farther from its trust-law roots?

If a change:

- Expands opacity,

- Normalizes illiquidity without valuation safeguards,

- Relies on exemptions over bright lines,

- Or makes challenges harder for beneficiaries,

then it functionally weakens ERISA, even if the statute’s words remain untouched.

The through-line

From 1933 to 1940 to 1974, Congress responded to financial abuse the same way:

force sunlight, ban conflicted structures, empower beneficiaries.

When modern policy trends move in the opposite direction—toward complexity, exemptions, and reduced accountability—they don’t repeal those laws.

They hollow them out.

That is the quiet erosion this article warns about.

/