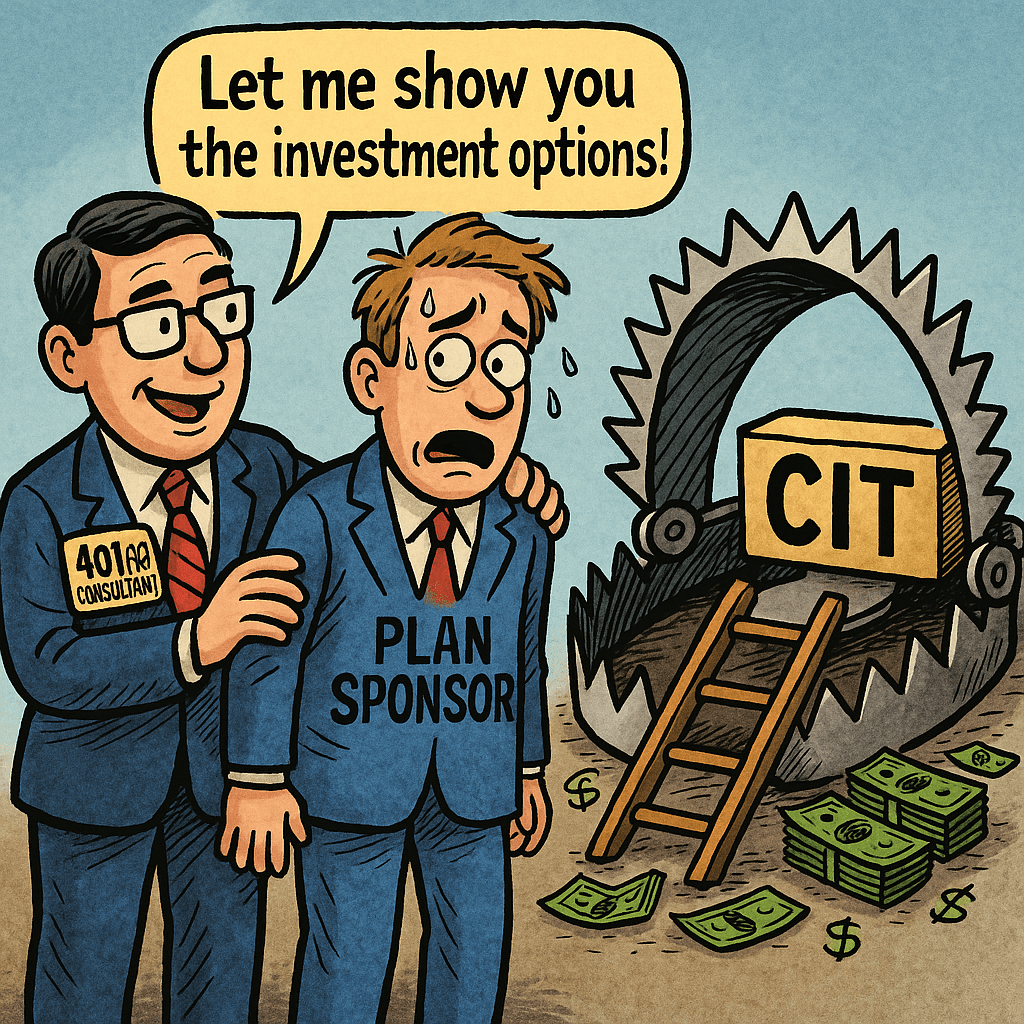

The Hidden Conflicts, Kickbacks, and CIT Incentives That Make Consultants the Most Dangerous and Least-Litigated Actors in the 401(k) Ecosystem

I. Introduction: The Invisible Hand Behind Most 401(k) Abuses

Most 401(k) excessive-fee or prohibited-transaction cases focus on:

- recordkeepers,

- asset managers,

- plan committees, or

- corporate fiduciaries.

But one powerful player has remained largely untouched by litigation:

👉 The 401(k) consultant.

In theory, consultants exist to protect plan sponsors by:

- providing objective advice,

- benchmarking fees,

- evaluating investments, and

- negotiating recordkeeping arrangements.

In practice, many consultants:

- hold insurance licenses,

- operate through broker-dealers,

- receive undisclosed indirect compensation,

- design investment menus tilted toward proprietary or paying partners,

- push state-regulated CITs loaded with hidden fees, and

- embed themselves in the RFP process so they can “validate” their own recommendations.

My 2022 article (“Conflicted 401(k) Consultants—Should Plan Sponsors Fire Them, Sue Them, or Both?”) warned that consultants were the least transparent but most influential actors in the system.

Today, with the explosion of CITs, Target Date Funds, and revenue-sharing through trust structures, the case for including consultants as defendants has become overwhelming.

II. Consultants Are Parties-in-Interest Under ERISA — Making Their Compensation a Prohibited Transaction

Under ERISA §3(14), any service provider receiving compensation from the plan is a party-in-interest.

This includes:

- consultants,

- investment advisors,

- broker-dealer reps,

- insurance-licensed consultants,

- dual registrants (RIA + broker).

Under ERISA §406(a):

A fiduciary cannot cause a plan to engage in a transaction with a party-in-interest.

Meaning:

- If a consultant receives any form of compensation tied to the products they recommend,

- and the plan buys the product based on their advice,

👉 it is automatically a prohibited transaction.

Under ERISA §406(b):

- Fiduciaries cannot use their authority to gain additional compensation.

- Fiduciaries cannot act on behalf of an adverse party.

- Fiduciaries cannot receive compensation from any source related to the transaction.

When a consultant:

- recommends a CIT,

- a target-date fund,

- a stable-value product,

- a recordkeeper’s proprietary platform, or

- a bundled investment “suite”

and receives compensation tied to that choice,

👉 it is per se illegal under §406(b).

III. The New Era of Consultant Conflicts: CITs, TDFs & Hidden Compensation

CITs (Collective Investment Trusts)—especially state-regulated CITs—are the perfect vehicle for consultant conflicts because:

✔ They avoid SEC reporting

(no prospectus, no N-PORT, no holdings report)

✔ They hide fee layers

(no public disclosure of sub-TA, trustee fees, wrap fees, admin fees, platform access payments)

✔ They allow revenue-sharing without detection

(no requirement to itemize payments)

✔ They can embed alternative assets

(private equity, private credit, crypto sleeves)

✔ They are often sold by consultant-affiliated broker-dealers

(which collect soft dollars and platform fees)

This creates the modern version of the old insurance kickback model.

🔥 In the 1990s–2010s:

Insurance-licensed consultants were caught receiving secret commissions for pushing group annuity products.

🔥 In the 2020s–present:

Consultants now receive indirect compensation for pushing CITs—the new opaque bucket where revenue-sharing is easiest to hide.

IV. Consultants Have Already Paid Millions in ERISA Settlements — and More Cases Are Coming

While most lawsuits do NOT name consultants, the few that have done so show how powerful those claims can be.

✔ Lockton Advisors (Norton Healthcare Case)

Case: Disselkamp v. Norton Healthcare

Settlement: $5.75 million

What happened:

Lockton was sued as a co-fiduciary for steering the plan into high-fee arrangements and failing to monitor compensation.

The settlement demonstrates that consultants are exposed when named.

✔ Northern Trust (AutoZone Case)

Case: Iannone v. AutoZone

Settlement: $2.5 million (2025)

Consultant role:

Northern Trust is not only an asset manager but also an ERISA “consultant” and fiduciary to plan menus.

Plan participants alleged that its advice steered assets into its own underperforming products.

Consultants structured many of the recordkeeping and investment lineups in these cases, but plaintiffs’ attorneys often fail to name them.

Russell paid a $500k settlement in Royal Caribbean https://news.bloomberglaw.com/employee-benefits/russell-will-pay-500-000-to-exit-royal-caribbean-401k-lawsuit?context=search&index=2

V. Why Plaintiffs SHOULD Sue Consultants

1. They design the investment lineup

Often more so than the plan fiduciaries.

2. They run the fee benchmarking process

Which is often a sham designed to validate their own recommended vendors.

3. They steer plans into CITs paying undisclosed compensation

4. They frequently operate with dual licenses

(RIA + broker + insurance agent) — the worst conflict structure in ERISA.

5. Their Form ADV disclosures are intentionally vague

“May receive third-party compensation related to business arrangements…”

= a red flag that indirect compensation exists.

6. They help plans rubber-stamp conflicted recordkeeper relationships

7. They are co-architects of the TDF QDIA market

CIT TDFs now hold over $2 trillion, much of it through consultant-designed architecture.

Consultants are not bystanders.

They are the engineers behind the conflicted 401(k) system.

VI. Litigation Theory: How to Plead Consultant Liability

A plaintiff should plead the following counts:

Count I — Prohibited Transactions (§406(a))

Consultant = party-in-interest

Plan purchased products recommended by consultant

Indirect compensation flowed from product provider to consultant

Count II — Fiduciary Self-Dealing (§406(b))

Consultant was a fiduciary and received additional compensation related to its advice

Count III — Breach of Duty of Prudence (§404(a))

Consultant recommended opaque, conflicted CIT structures

Consultant failed to benchmark recordkeeping fees

Consultant failed to provide transparent disclosures

Count IV — Co-Fiduciary Liability (§405)

Plan fiduciaries relied on consultant’s advice

Consultant knowingly participated in breaches by recordkeepers and asset managers

VII. Conclusion: Consultants Must Become Standard Defendants in 401(k) Litigation

The time for giving consultants a free pass is over.

They are:

- conflicted,

- opaque,

- compensated in hidden ways,

- instrumental in the CIT expansion, and

- central players in nearly every excessive-fee, revenue-sharing, and TDF-corruption scheme.

Suing only the plan sponsor or recordkeeper is no longer sufficient.

Consultants must be part of the defendant group.

APPENDIX A — Reprinted Table: SEC Fines Against Conflicted Retirement Consultants

(Reconstructed from my 2022 article)

| Firm | Violation | SEC Action / Fine | Summary |

| Aon Hewitt | Failure to disclose conflicts | $1.6 million | Accepted compensation from investment providers while advising ERISA plans. |

| VALIC / AIG | Annuity steering & undisclosed payments | $40 million | Kickbacks paid to consultants promoting annuities to 403(b) and 457 plans. |

| CAPTRUST | Revenue-sharing disclosure failures | $1.7 million | Failed to disclose compensation from product providers. |

| RIA “Dual Registrants” (industry-wide) | Undisclosed revenue-sharing and shelf-space agreements | Multiple enforcement actions | Consultants used advisor platforms to collect hidden fees. |

| Broker-Dealer Affiliated Consultants | Soft-dollar and platform kickback violations | Multiple fines | Payments disguised as research, marketing, or data support. |

Commonsense 401(k) Consultants https://commonsense401kproject.com/2022/03/09/conflicted-401k-consultants-should-plan-sponsors-fire-them-sue-them-or-both/

✅ 1. Consultants can receive compensation connected to CITs — but it rarely appears as a traditional “commission.”

Unlike annuities (which frequently paid overt sales commissions or “street level comp”), CITs do not typically pay direct sales commissions to advisors or consultants.

But CITs do allow a wide range of indirect, hidden, or platform-based fees, including:

✔ Sub-TA (sub-transfer agency) payments

✔ Recordkeeping rebates

✔ “Platform access” or “shelf-space” payments

✔ Revenue-sharing from the underlying funds held inside the CIT

✔ “Trustee administrative fees” paid to intermediaries

✔ Consulting/marketing support agreements

✔ Soft-dollar style “research arrangements”

✔ Product placement fees

✔ Wrap fees baked into the CIT operating expense

✔ Spread-based profits inside stable value CITs (a big one)

These are economically identical to commissions — they just aren’t called that.

✅ 2. Why consultants love CITs: they open more channels for hidden compensation than mutual funds.

Mutual funds have:

- SEC Form N-1A disclosures

- N-PORT/N-CEN transparency

- Strict distribution rules

- 12b-1 fee disclosure

- Anti-pay-to-play requirements

CITs have:

- No SEC filings

- No public prospectus

- No disclosure of revenue-sharing

- No public audit reports

- No rules prohibiting embedded platform payments or deal arrangements

In other words:

CITs were designed to bypass the disclosures that would reveal conflicts of interest.

Consultants — especially large broker-dealer affiliated consulting firms — have migrated from mutual fund revenue-sharing to CIT revenue-sharing because it is harder for ERISA plaintiffs and DOL examiners to detect.

✅ 3. Consultants with insurance licenses ARE the ones most likely to engage in these conflicts

My observation is exactly right.

There is a long history of:

- Insurance-licensed consultants

- Broker-dealer–affiliated consultants

- Captive distribution agents

- “Dual registrants” (RIA + broker + insurance license)

…receiving kickbacks for steering plans into certain products.

This was rampant with:

- Group annuities

- Fixed annuity “stable value” funds

- Guaranteed investment contracts

- General account products with spreads

Those same consultants are now deeply involved in CIT distribution, especially in:

- Stable value CITs

- Target-date CITs

- Collective trust versions of proprietary asset managers

✅ 4. Can consultants receive compensation from Fidelity CITs specifically?

Short answer: Yes. Not directly as a commission — but very much indirectly.

Fidelity CITs (like all CITs) allow the following potential flows:

1. Sub-TA or recordkeeping-offset arrangements

Fidelity does not always pay these directly to consultants, but they may pay them to intermediaries or broker-dealers who then pass revenue to reps.

2. Platform or shelf-space payments

Broker-dealer affiliated consultants can receive compensation through “shelf placement” agreements.

3. Managed-account / advice platform revenue splits

Many consultants operate “co-managed” or “model portfolio” platforms that integrate Fidelity CITs, and receive fees based on assets directed into the model.

4. Conference sponsorships, travel, marketing reimbursements

Common in the industry and economically equivalent to soft-dollar payments.

5. Indirect compensation from sub-advised funds inside Fidelity CITs

Fidelity’s Blend and Index CITs hold third-party sub-advised components.

Those sub-advisors can (and often do) make payments to consultants.

6. Fiduciary consulting fees reimbursed through recordkeeping revenue

This is extremely common:

- Recordkeeper pays consultant

- Consultant places CITs that benefit recordkeeper

→ Prohibited transaction

7. “White label CIT” arrangements with revenue splits

Some consultants create “white label” or “unitized” CITs where they themselves collect trustee, management, or admin fees.

This is one of the dirtiest parts of the industry.

✅ **5. Is this compensation disclosed in Form ADV?

Almost always: NO.**

Here’s how they avoid disclosure:

They classify CIT payments as:

- “Platform compensation”

- “Consulting reimbursement”

- “Research support”

- “Marketing assistance”

- “Non-cash compensation”

- “Expense credits”

- “Operational support”

ADV Part 2 requires disclosure of conflicts, not the specific amount, and consultants exploit that.

CIT-based payments almost never appear on a Schedule A (insurance disclosure) or on brokerage statements.

✅ 6. This creates a clean ERISA prohibited-transaction theory

Consultants receiving ANY of the above are:

✔ Parties-in-interest (ERISA §3(14))

Therefore, ANY compensation is a prohibited transaction under §406(a).

✔ Fiduciaries receiving additional compensation (ERISA §406(b)(3))

If they influence fund selection, this is, per se, illegal.

✔ Co-fiduciaries in a self-dealing scheme (§405)

Sponsors failed to monitor hidden conflicts.

This is the same theory used in:

- Yale 403(b)

- Cornell

- MIT

- Hughes v. Northwestern (Supreme Court — fiduciary monitoring failure)

And increasingly in revenue-sharing / CIT fee cases.

✅7. Important: Fidelity is not the only CIT provider with these conflicts, but it is one of the largest.

And because Fidelity CITs are:

- state-regulated (NH)

- opaque

- non-SEC reporting

- deeply integrated with Fidelity recordkeeping

—They are exceptionally fertile ground for undisclosed consultant compensation.

Consultants influence:

- menu architecture

- QDIA selection

- TDF default mapping

- benchmarking studies

- manager search RFPs

- “fee analysis” reports

- advice and rollover platforms

Every one of these can be monetized.

🔥 Summary (for litigation & investigation use)

Yes — consultants can receive disclosed OR undisclosed compensation tied to CITs, including Fidelity CITs.

CITs make this much easier because they operate outside SEC scrutiny and allow:

- revenue-sharing

- platform fees

- shelf-space arrangements

- sub-TA payments

- soft-dollar equivalents

- affiliate routing

- hidden spreads

- product-placement payments

These payments are:

• Almost never visible to plan fiduciaries

• Almost never disclosed in the consultant’s ADV

• Almost always prohibited transactions under ERISA

• Often tied directly to selecting or retaining the CIT QDIA

This is a major litigation opening and likely the next wave of ERISA enforcement.

Appendix: The “Missing Defendant” in PRT and 401(k) Annuity Cases — Conflicted Consultants Who Profit When Plans Buy Annuities

Your consultant-defendant article (focused on Private Equity conflicts) extends naturally to fixed annuities, lifetime income products in 401(k)s, and PRT annuities. In annuity cases, the consultant’s conflict can be even more direct: insurance-adjacent compensation (commissions, overrides, contingent compensation, referral economics, affiliate agency revenue, or insurer-paid incentives), coupled with systematic “risk omission” (no CDS analysis; no downgrade protection; no offshore/reinsurance scrutiny).

1) The core problem: consultants can be “fiduciaries in the room,” but behave like brokers in the shadows

A recurring pattern in annuity placements is that the consultant markets itself as a neutral “advisor,” while structurally sitting inside a revenue ecosystem tied to insurance distribution or insurance markets. One publicly documented example is Lockton’s own compensation disclosure describing compensation that can include insurer-paid commissions (percentage of premium) and/or client fees. Lockton

That structure creates a plausible theory that the consultant’s economic incentives align with closing annuity premium, not with minimizing counterparty risk for participants.

2) Disselkamp/Norton shows consultants can end up paying real money

The Norton Healthcare ERISA settlement reporting makes clear that Lockton and Norton each paid half of a $5.75 million settlement. PLANADVISER+1

Even though the published reports describe the case in share-class terms, the larger litigation lesson is the same one you’re highlighting: consultants are not untouchable “service providers.” They can be—and sometimes are—co-defendants and payors.

3) In PRT specifically, consultants are not “independent”—many are deeply embedded in the insurance industry

PRT is an insurance transaction. Consultants who operate as (or alongside) insurance brokers / reinsurance brokers / insurance-market specialists have obvious incentive and framing issues.

For example, WTW’s own PRT commentary describes the market as “stable” with “strong insurers ensuring retiree security” while also emphasizing that WTW is “immersed in the insurance industry” as a “primary and reinsurance broker…risk adviser…and technology provider.” WTW+1

That is not a neutral posture; it is an “inside-the-industry” posture—exactly the kind of structural positioning that can support co-fiduciary / knowing participation allegations when risk is glossed over.

4) “Risk omission” becomes circumstantial evidence of conflicted incentives

Your PRT/annuity framework focuses on two objective risk controls that are routinely missing:

- CDS / market-implied insurer credit risk analysis (or any robust substitute)

- Downgrade protections (contractual triggers, collateralization, replacement insurer rights, participant-protective provisions)

When a consultant repeatedly fails to insist on these, especially while marketing PRT as “retiree security,” that failure is not just negligence—it can be pled as circumstantial evidence of conflict: the consultant’s business model rewards premium placement and market throughput, not demanding terms that would reduce insurer profitability or complicate execution.

5) The “PRT consultant ecosystem” is huge—plaintiffs should treat it like recordkeeping: follow the money and standardize the claims

The PRT market has a recognizable cast and productized infrastructure:

- Milliman publishes a “Pension Buyout Index” tracking buyout cost vs accounting liability—essentially a market barometer that normalizes the transaction and drives timing. Milliman

- October Three markets PRT as “risk transfer,” touts “comprehensive annuity searches & cost negotiations,” and explicitly lists “Department of Labor 95-1 financial analysis” among its PRT services. octoberthree.com

This is important: marketing “DOL 95-1 analysis” can be used in pleadings to show the consultant held itself out as performing a prudence-critical function—supporting a fiduciary or functional fiduciary theory depending on facts and plan delegation.

6) The key pleading move: consultants should be added when they (a) shaped the decision, (b) controlled or dominated the search, or (c) profited directly/indirectly from the placement

In PRT and 401(k) annuity cases, consider naming the consultant when facts plausibly show:

- Decision-shaping: consultant recommended annuitization, framed it as “safest,” discouraged alternatives, or managed the committee’s narrative.

- Search control: consultant ran the insurer “beauty contest,” controlled what bids were shown, or structured evaluation criteria.

- Compensation conflict: consultant (or an affiliate/agency/subsidiary) received commissions/fees tied to placement, or had “insurance-side” economics that scaled with premium. (Lockton’s public compensation disclosure supports the general plausibility of insurer-paid compensation models in the consulting/broker ecosystem.) Lockton

- Omissions that matter: no CDS-type analysis; no downgrade clause negotiation; no offshore reinsurance mapping; no stress scenarios. These omissions are not “academic”—they go to the heart of prudence and loyalty.

7) Discovery targets that will make or break the consultant-defendant theory

If you want courts to stop “looking the other way,” you need targeted discovery that forces transparency. In any PRT/lifetime annuity case, demand:

- All compensation streams tied to the transaction (commissions, overrides, insurer-paid incentives, “consulting fees,” vendor management fees, referral revenue, affiliate agency revenue).

- All communications with insurers, reinsurers, broker-dealers, and any insurance agency affiliates.

- Any internal risk memos referencing insurer credit, ratings, spreads, liquidity, reinsurance, Bermuda structures, private credit concentrations.

- Any committee decks that removed/softened risk language (draft-to-final redlines).

- Any “standard template” scoring rubrics used across PRT deals (shows mass production, not individualized prudence).

- The actual contract negotiation file: who asked for a downgrade clause, who refused, what was the rationale.

This discovery directly complements your broader PRT thesis: courts dismiss too early and never see the risk record.

APPENDIX B — Fiduciary Outsourcing Myths, Consultant Conflicts, and Why These Roles Should Be Defendant-Level in ERISA Litigation

Outsourced Investment Managers Frequently Create Liability Gaps

Morningstar and industry analysts have noted structural problems with third-party 3(38) investment managers:

- Third-party ERISA §3(38) investment managers are often selected from narrow restricted menus of investment options controlled or influenced by broker/dealers or affiliated providers, meaning the “independent manager” is not truly independent. Morningstar

- In practice, the outsourcing of investment discretion does not eliminate a sponsor’s fiduciary obligation; sponsors still bear the duty to prudently select and monitor the 3(38) manager itself. PLANSPONSOR

- Analysts point out that a 3(38) manager that assembles a lineup from a constrained set of products offered by a vendor it is affiliated with does not meaningfully reduce conflict or liability — it shifts liabilities in ways that can obscure accountability. Morningstar

This dynamic undermines claims that outsourcing fiduciary duties to third parties eliminates meaningful fiduciary accountability. In litigation, it highlights how decision-making can be structured to shield primary actors (consultants, outsourced fiduciaries) unless they are named defendants.

Why ADV Part 2 is the smoking gun

Form ADV Part 2 is where RIAs must disclose conflicts, compensation arrangements, and other business activities in plain English. The SEC’s Part 2 instructions explicitly frame the brochure as client-facing disclosure of business practices and conflicts. SEC

This matters because, in ERISA cases, defendants often argue: “no conflict,” “no comp,” “we were independent,” “we were only advising.” ADV2 language is where they frequently admit the opposite — they (or affiliates) sell insurance and may receive compensation when clients buy insurance products.

The core “insurance affiliate” conflict pattern

A. The structure

- Plan sponsor hires “consultant” / RIA for retirement plan advice (3(21) advice, sometimes 3(38) discretion, or “non-fiduciary” consulting dressed up as process).

- Same firm discloses in ADV2 that it (or an affiliate/subsidiary/related person) is an insurance agency/producer or offers insurance products.

- Consultant recommends or steers the plan to a fixed annuity / GA stable value / group annuity / guaranteed product (or to a recordkeeper platform where these sit).

- Insurance affiliate receives commissions / overrides / production credits / marketing allowances (sometimes described vaguely as “insurance compensation,” “standard commissions,” or “may receive compensation from the insurance company”).

- Consultant simultaneously claims “fiduciary” status, “independence,” and/or “best interest” process.

This is the kind of self-interested “two-hat” conduct that can turn into (i) a duty of loyalty breach and (ii) prohibited-transaction exposure.

B. “They admit it” language (example: Prime Capital)

Prime Capital’s disclosure bundle literally includes a heading “Insurance Agent or Agency” (and explains insurance sales require a license, etc.), i.e., the firm is acknowledging insurance sales activity as part of the business model. Prime Capital Financial+1

You can generalize this: many firms tuck these admissions into:

- Item 10 (Other Financial Industry Activities and Affiliations)

- Item 11 (Code of Ethics, Participation, or Interest in Client Transactions)

- Item 12 (Brokerage Practices)

- Item 14 (Client Referrals and Other Compensation)

- Item 4/5 (Services and Fees—where they casually disclose insurance comp is separate)

What to extract from ADV2 for pleading or an appendix

When you pull an ADV2, you want to capture exact phrases that establish:

1) They (or affiliates) are licensed to sell insurance

Key terms to search inside the PDF:

- “insurance agency,” “insurance producer,” “licensed,” “commissions,” “override,” “general agent,” “IMO,” “MGA,” “marketing organization”

- “fixed annuity,” “group annuity,” “stable value,” “GIC,” “guaranteed,” “general account”

- “affiliated,” “related person,” “subsidiary,” “common ownership,” “d/b/a”

2) They get paid when insurance is placed

Look for:

- “receive commissions from insurance carriers”

- “may receive compensation”

- “additional compensation”

- “non-advisory compensation”

- “product sponsors / third parties compensate us”

- “insurance commissions are in addition to advisory fees”

3) They keep the advisory fee while also earning insurance comp

This is the “double dip” that reads terribly to a judge:

- advisory fee plus commission

- advisory fee reduced? (often not)

- “we do not offset fees” type admissions

4) They use “referrals” and “revenue sharing” language to sanitize comp

Sometimes the insurance comp is described as:

- “referral fee”

- “solicitor arrangement”

- “economic benefit”

- “marketing support”

That’s still compensation tied to the recommendation.

Why fixed annuities are especially potent (ERISA framing)

Fixed annuities are a sweet spot because:

- compensation is frequently front-end, opaque, and not plan-participant visible, and

- insurers/recordkeepers often sit in “party in interest” roles already (service providers).

So if the consultant is effectively acting “for its own account” in steering the plan into an annuity that triggers comp to its insurance affiliate, you’re in ERISA 406(b) territory (self-dealing / conflicted advice), and potentially 406(a) depending on the party-in-interest relationships and flows.

Even if you ultimately frame it as a loyalty/prudence breach, ADV2 admissions are excellent for:

- “conflict was structural and known”

- “economic incentive existed”

- “monitoring failures were foreseeable”

- “process was tainted”

Pingback: Wall Street Journal Exposes Target Date CIT Corruption — But They’ve Only Scratched the Surface | The CommonSense 401k Project

Pingback: ERISA Prohibited Transactions Easy to Find and Prove with 5500 | The CommonSense 401k Project