Employee-owned, publicly traded, or PE-backed—every major consultant now has financial incentives to push higher-fee private equity and private credit.

For years, institutional investment consultants have marketed themselves as independent fiduciaries guiding pension funds, 401(k) plans, endowments, and public retirement systems through the complexities of modern markets.

But the truth is far different. In 2025, the consulting industry has quietly transformed into the single most important distribution channel for private equity.

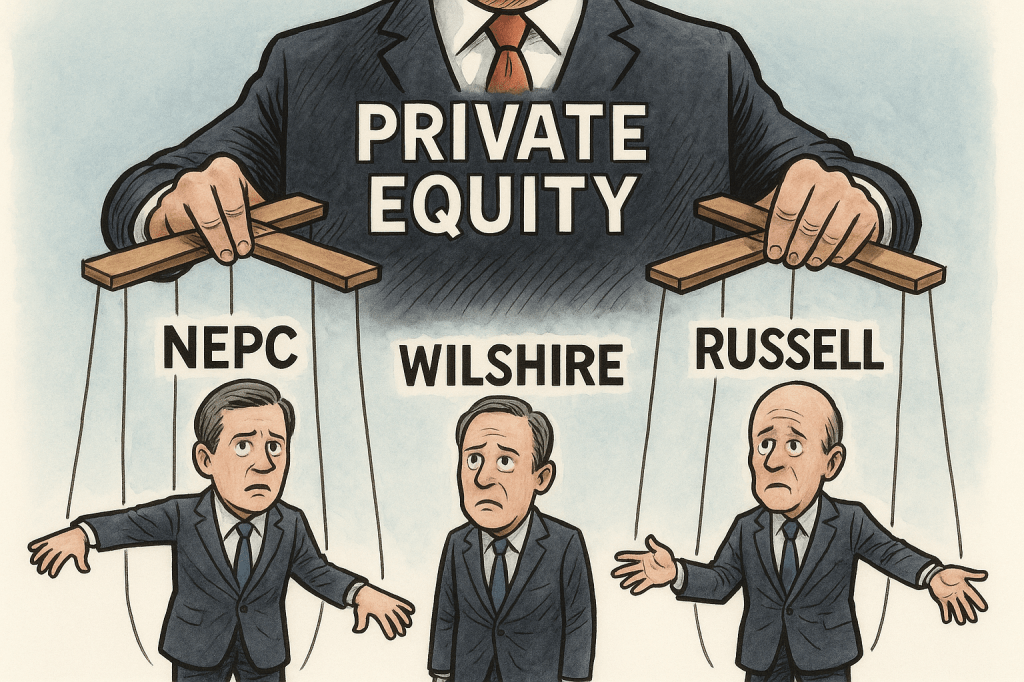

This shift cuts across every ownership model:

- PE-owned consultants like NEPC (via Hightower/THL), Wilshire (CC Capital & Motive Partners), Russell Investments (TA Associates & Reverence Capital), and SageView (Aquiline).

- Public-company-owned consultants like Mercer (Marsh & McLennan), Aon, and WTW—with earnings models tied to alternatives growth.

- Employee-owned consultants like Callan, Meketa, RVK, Verus, and Marquette, who rely on higher-priced alternative consulting services to drive revenue and consultant compensation.

Whether PE-owned or “independent,” the economic incentives all point in the same direction:

Push pensions and retirement plans into higher-fee private equity and private credit—regardless of long-term risk to beneficiaries.

PE-Owned Consultants: Conflict at the Core

NEPC – Now indirectly PE-controlled

In 2025, Hightower Holding acquired a majority stake in NEPC. Hightower is itself majority-owned by private equity firm Thomas H. Lee Partners.

This means NEPC—long positioned as a “fiduciary-only” advisor—is now part of a private-equity-backed distribution platform.

Wilshire Advisors – Apollo’s footprint via Motive & CC Capital

Wilshire was taken private by Motive Partners and CC Capital, whose leadership and capital partners maintain deep ties to Apollo and the private markets ecosystem.

Wilshire has since pivoted aggressively toward alternatives advisory and OCIO mandates.

Russell Investments

Owned by TA Associates (majority) and Reverence Capital Partners, Russell is one of the largest OCIO platforms in the world. It profits directly when clients allocate more to alternatives under its discretionary management.

SageView Advisory Group (Aquiline)

For several years, private equity firm Aquiline Capital Partners held a controlling stake in SageView. Aquiline’s strategy: consolidate RIAs and drive asset growth into high-margin private-market solutions.

In short:

When the owners of a consultant profit from private equity, the advice will inevitably steer clients toward private equity. Angeles Investment Advisors owned by PE firm Levine Leichtman Capital Partners. Prime Bucholz has been in minority partnerships with PE over the years.

Publicly Traded Consultants: Shareholders Demand Alternatives Growth

Even consultants not owned by private equity have public shareholders pushing them toward higher-margin advisory services—namely private equity, private credit, and OCIO.

Mercer (owned by Marsh & McLennan)

Mercer operates one of the largest:

- OCIO businesses in the world

- Proprietary private equity funds-of-funds

- Alternative investment research and distribution groups Mercer Alternatives bought Pavillion from PE firm TriWest Capital Partners in 2018, and still influences platform.

Mercer earns much higher fees for:

- Private markets due diligence

- Access to Mercer-managed PE vehicles

- OCIO discretionary mandates

Marsh & McLennan’s investor calls make it clear: alternatives and OCIO growth drive shareholder value.

Aon

Aon aggressively markets:

- Aon Private Markets

- Aon Private Credit solutions

- Aon OCIO

Aon’s 10-K filings explicitly list “delegated investment management” and private markets as key revenue drivers.

WTW (Willis Towers Watson)

WTW operates its own private equity platform:

- WTW Private Equity Solutions

- Commingled alternative funds

- Infrastructure/real asset vehicles

WTW extracts multiple layers of fees when a pension allocates to alternatives through their platform.

Conclusion:

Mercer, Aon, and WTW have financial obligations to public shareholders that directly incentivize recommending higher-fee private equity allocations. Rocaton was bought by Goldman Sachs a firm deeply embedded in private equity

Employee-Owned Firms: Clean Ownership, Dirty Incentives

This is the category most trustees and regulators mistakenly assume is “independent.”

But employee-owned consultants still have major conflicts of interest tied to private equity fee structures.

Callan – Pay-to-Play Through Callan College

Callan promotes itself as independent and employee-owned. Yet:

- Callan College allows asset managers—including private equity firms—to pay for access to plan sponsors.

- Callan charges premium fees for alternatives consulting.

This creates a baked-in incentive to recommend private equity.

Meketa – Higher Fees for Private Markets

Meketa earns:

- Standard fees for public markets consulting

- Much higher fees for private equity, private credit, and hedge fund oversight

Plus, Meketa markets itself as a leader in private markets advisory, turning private equity consulting into a profit engine.

RVK, Verus, Marquette, Cliffwater, Aksia, Albourne Partners, Segal, Cambridge – Similar Incentives

These firms:

- Charge materially higher fees for alternatives consulting

- Promote themselves as experts in private markets

- Benefit through staff growth and enhanced margins when clients increase private equity allocations

Even without PE owners, the internal compensation systems reward consultants who grow alternatives business. Others with substantial conflicts around PE include CEM, Global Governance Advisors, and Funston.

The Industry-Wide Conflict: Alternatives = Higher Fees

Across all ownership structures, the economic truth is the same:

| Consultant Type | Why They Push Private Equity |

| PE-Owned (NEPC, Wilshire, Russell, SageView) | Owners expect private equity–driven revenue growth |

| Publicly Traded (Mercer, Aon, WTW) | Shareholders demand higher-margin alternatives & OCIO |

| Employee-Owned (Callan, Meketa, RVK, Verus, Marquette) | Higher consulting fees; pay-to-play structures; prestige and internal incentives |

APPENDIX 1

How Consultants Use Smoothed Returns to Justify Overallocations to Private Equity and Private Credit

Summary

Pension consultants systematically overallocate to private equity and private credit not because these assets demonstrably improve risk-adjusted outcomes, but because smoothed, appraisal-based return data mechanically overstates returns and understates risk in asset-allocation models. This distortion aligns with consultants’ economic conflicts and effectively turns asset-allocation modeling into a distribution mechanism for high-fee private assets.

1. Smoothed Returns Are a Known, Documented Problem

Illiquid private assets do not trade continuously and are typically valued using appraisals, models, or manager-supplied marks. This produces stale and artificially smoothed return series.

The CFA Institute (2025) explicitly warns that analysts must test for serial correlation and states that analysts “need to unsmooth the returns to get a more accurate representation of the risk and return characteristics of the asset class.”

Failure to unsmooth causes:

- Understated standard deviation (volatility)

- Artificially low correlation to public markets

- Inflated Sharpe ratios

- Illusory diversification benefits

This is not controversial; it is widely accepted in the academic and professional literature.

2. Optimization Models Convert Smoothing into Overallocation

Consultants then feed these distorted inputs into:

- mean-variance optimization,

- risk-parity frameworks, or

- efficient frontier analyses.

When an asset shows:

- high historical returns,

- low reported volatility, and

- low correlation,

optimization must recommend a larger allocation. The result is mathematically predetermined.

In other words, the model is not discovering diversification—it is laundering volatility.

3. Academic Evidence Confirms the Distortion

The 2019 SSRN paper “Unsmoothing Returns of Illiquid Assets” (Couts, Gonçalves, and Rossi) demonstrates that commonly used unsmoothing techniques are often inadequate and that true risk exposures—especially market beta and downside risk—are materially higher than reported.

Once proper unsmoothing is applied:

- correlations to public equities rise,

- volatility increases,

- and much of the apparent alpha disappears.

This finding directly undermines consultant claims that private equity and private credit offer persistent, low-risk diversification benefits.

4. Why This Serves Consultant Conflicts

As documented in How America’s Largest Pension Consultants Became the Distribution Arm for Private Equity, consultants often have:

- ownership ties to private-market platforms,

- revenue relationships with private managers,

- internal compensation incentives linked to alternatives adoption.

Smoothed returns provide the technical justification for conflicted recommendations. They allow consultants to present sales outcomes as fiduciary analytics.

This same logic applies to private credit, where appraisal-based pricing and delayed loss recognition further suppress volatility and correlation—despite operating in highly competitive credit markets where true excess returns are measured in basis points.

5. Fiduciary Implications

Asset-allocation decisions based on smoothed private-market returns:

- overstate expected returns,

- understate portfolio risk,

- misrepresent diversification benefits,

- and systematically bias portfolios toward high-fee private assets.

From a fiduciary perspective, an allocation recommendation that collapses once returns are properly unsmoothed is not prudent—it is misleading.

6. Minimum Disclosures Fiduciaries Should Demand

Any consultant recommending private equity or private credit should be required to provide:

- Serial-correlation diagnostics on private-asset returns

- Full disclosure of unsmoothing methodology and parameters

- Asset-allocation results before and after unsmoothing

- Changes in volatility, correlation, and beta post-unsmoothing

- A clear explanation of how much of the recommended allocation depends solely on smoothed data

Absent these disclosures, claims of diversification and superior risk-adjusted returns lack credibility.

Appendix 2 : Incentive Misalignment in Private Markets — Insights from CFA Institute Blog Analysis (Jan. 7, 2026)

The CFA Institute’s Blog in January 2026 by Mark Higgins CFA is an analysis of private markets reveals structural incentive dynamics that strongly reinforce the concerns raised in this article about how major pension consultants function as distribution channels for private equity and private debt, often without commensurate improvements in value, transparency, or fiduciary outcomes. CFA Institute Daily Browse https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2026/01/07/incentives-are-dangerously-aligned-in-private-markets/ (opinion of author not an official position of CFA Institute. Higgins did another piece on conflicted consultants in 2024 https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2024/01/25/the-conflict-of-interest-at-the-heart-of-investment-consulting__trashed/

1. Systemic Incentives Drive Supply Expansion Over Prudence

The CFA Institute piece characterizes the private markets “supply chain” as a **system driven by near-perfect incentive alignment among participants that encourages ever-greater production of private-market vehicles while de-emphasizing underwriting discipline and risk restraint.” CFA Institute Daily Browse

This dynamic applies directly to pension consultants. Once consultants expand roles from independent performance reporters into architects of portfolio design (especially alternative allocations), their professional incentives shift toward increasing portfolio complexity and assets under advisory — because:

- Compensation and reputation become tied to the scale and complexity of allocations rather than outcomes.

- With private market allocations embedded into policy targets, deviating toward simpler, lower-cost portfolios carries career risk.

- Consultant forecasts and capital markets assumptions themselves can rise in tandem with private markets allocations — even as underlying returns lag expectations. CFA Institute Daily Browse

This precisely matches the pattern the CFA Institute warns about: incentives to expand product adoption overshadow incentives to ensure prudence or transparency. CFA Institute Daily Browse

2. Consultants Have Become Structural Amplifiers of Private-Market Narratives

According to the CFA Institute analysis, one of the most dangerous aspects of the private-market ecosystem is when various actors — from advisors to trade media and academia — reinforce a growth narrative, giving “unearned legitimacy” to private market products. CFA Institute Daily Browse

For pension consultants, this confirms two troubling dynamics previously documented in this report:

- Consultants are highly influential in driving fund flows without evidence that their recommendations add value to plan sponsors. CFA Institute Daily Browse

- By evolving from independent analysts into portfolio constructors and allocators, consultants become part of the amplification machinery that promotes private market adoption, not just neutrally reports it — a conflict of interest the CFA Institute explicitly identifies. CFA Institute Daily Browse

Thus, consultants do not merely advise private market allocations; they structurally reinforce the narrative that these allocations are necessary, beneficial, and inevitable — even when systemic risks and performance realities suggest caution.

3. Structural Conflicts of Interest Echo Across the Supply Chain

The CFA Institute analysis frames private markets as a complex system in which no single actor fully comprehends compounding risk, yet each participant’s incentives promote expansion rather than discipline. CFA Institute Daily Browse

In the context of pension plans, this aligns with the critical observation that:

“Consultants now evaluate outcomes generated by portfolio architectures that they themselves design, reintroducing the same conflict of interest they originally sought to eliminate.” CFA Institute Daily Browse

According to CFA Institute:

- Structural incentive alignment among institutional allocators, fund managers, and distribution intermediaries has created a system in which risk segmentation and collective momentum override prudent risk analysis. CFA Institute Daily Browse

- Consultants are part of this alignment; their roles have expanded from independent evaluator to essential agent of product adoption — often without accountability for long-term outcomes. CFA Institute Daily Browse

4. The Speculative Supply Chain and Retirement Plans

The CFA Institute’s “speculative supply chain” analogy applies directly to pension plans and defined contribution vehicles:

- Private equity and private debt allocations have moved from niche alternatives into core portfolio components in many large plans. CFA Institute Daily Browse

- Once participation becomes routinized, collective incentives can orient toward preserving allocations rather than assessing whether those allocations truly benefit participants in net risk-adjusted, cost-adjusted terms. CFA Institute Daily Browse

- The narrative of illiquidity as sophistication and complexity as diversification is reinforced by administrators, advisors, consultants, and trade associations alike — exactly the type of amplifier behavior the CFA Institute warns about. CFA Institute Daily Browse

5. Evergreen and Semi-Liquid Structures — A Cautionary Parallel

Although not exclusively about consultants, the analysis highlights evergreen and semi-liquid structures as vehicles that warehouse risk, obscure valuation, and sustain the appearance of performance without transparent price discovery. CFA Institute Daily Browse

This structural design undermines the basic fiduciary principles of:

- fair valuation,

- periodic accountability, and

- participant protection — principles central to ERISA and to the prudent management of retirement plan assets.

That these vehicles are now widely marketed — and often recommended by pension consultants — reinforces why distribution is not neutral and why incentives matter for plan governance.

Pingback: Is Private Credit Performance a Fraud? | The CommonSense 401k Project

Pingback: Teacher Jim Vail’s Exposé on Chicago Teachers vs. Callan — A Case Study in Pension Consultant Capture | The CommonSense 401k Project