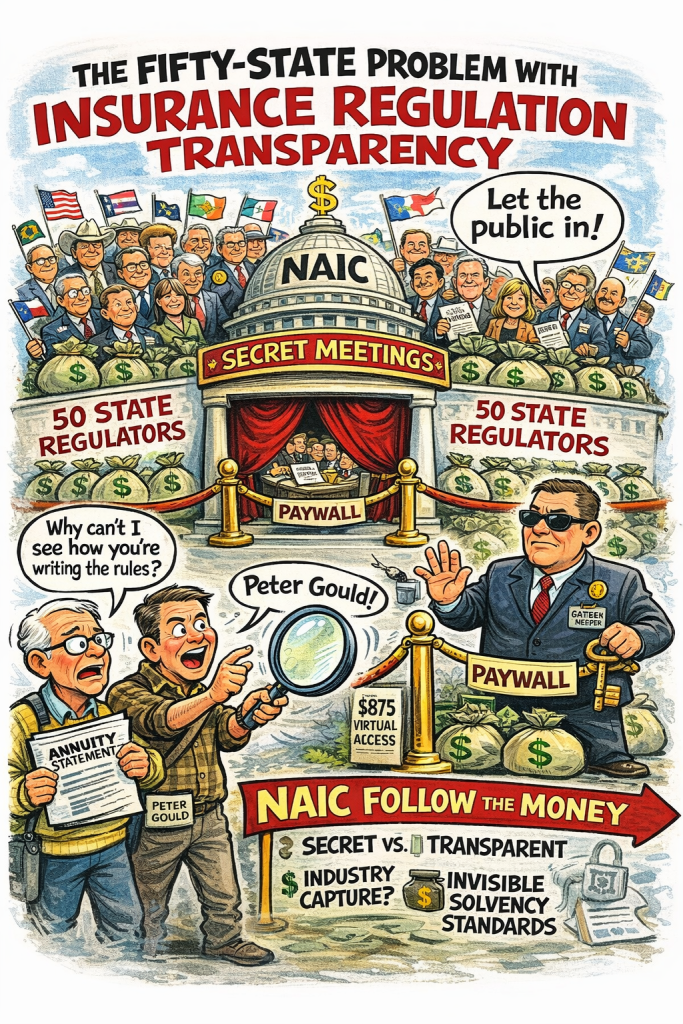

Insurance regulation in the United States is often described as “state-based.” That sounds reassuring. Local accountability. Fifty insurance commissioners. Fifty departments. Fifty sets of eyes.

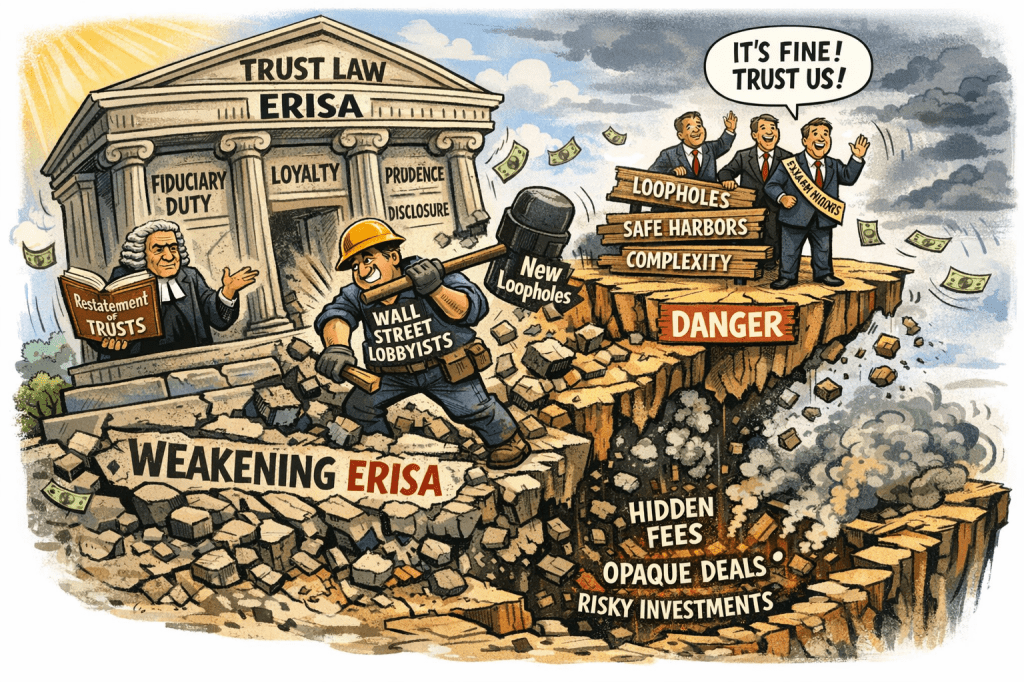

The reality is far less comforting. We have 50 separate regulators, each with its own budget constraints, political pressures, industry relationships, and transparency standards. There is no unified federal insurance regulator. No SEC-equivalent for life insurers. No ERISA-style fiduciary overlay governing retail annuities.

Instead, we have coordination through the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). And that’s where the real story begins.

The NAIC: The Quiet Nerve Center of Insurance Regulation

While insurance regulation is technically state-based, the NAIC writes the model laws, develops solvency standards, drafts accounting rules, and coordinates national policy.

State regulators almost uniformly adopt NAIC models. When NAIC moves, the states follow.

Which means this private, membership-based organization effectively shapes the rules governing:

- Trillions in life insurance reserves

- Over $2 trillion in individual annuity reserves

- The solvency standards protecting retirees

- The accounting treatment of general account assets

- The risk-based capital formulas that determine whether insurers survive or fail

And yet, for something that central, transparency has lagged far behind modern expectations.

The Velvet Rope Around “Public” Meetings

Peter Gould — a retiree and annuity contract owner — submitted a formal amendment proposal to the NAIC Executive Committee on August 7, 2025.http://petergould.com/PG-NAIC%20PROPOSED%20CHANGE-EC-MEETING%20ACCESS%20&%20RECORDINGS-2025-08-PROPOSAL%20&%20REDLINE%20AMENDMENT.pdf

His request is remarkably simple: If a meeting is designated “public,” then livestream it for free. Archive the recording. Post the materials.

No paywall. No $875 virtual attendance fee. No closed archive.

In his own words, Gould explains that as an annuity owner, he depends on regulators to proactively prevent insurer insolvency — yet he has no contractual rights to ensure that happens.

He is entirely dependent on regulatory competence and regulatory transparency. But if a retiree wants to virtually attend a public NAIC session, the cost can be hundreds of dollars. If he misses a meeting, the only official record may be curated minutes — which, as Gould notes, are a “summation rather than a complete transcript.”

The technology already exists. NAIC already livestreams internally. Webex links can be posted. Archiving is trivial. The barrier is not technical. It is institutional.

What Gould Is Actually Asking For

In his formal talking points submitted to the Executive Committee

, Gould outlines a proposal that would:

- Livestream all public meetings without charge

- Archive recordings and make them freely accessible

- Post meeting materials in a timely manner

- Maintain reasonable registration controls (but no payment requirement)

He notes that NAIC’s credibility depends on trust and broad stakeholder engagement — yet practical access barriers restrict participation to well-resourced entities and industry-paid lobbyists. That is the heart of the issue. If only large insurers and trade groups can afford full participation, the appearance — and perhaps the reality — becomes regulatory capture.

The Outdated Videotaping Policy

The current NAIC policy statement on videotaping dates back to 1998 and was revised in 2010. It predates the Webex era. It predates routine livestreaming. It predates modern digital transparency standards.

Gould’s redline amendment would modernize the policy to explicitly require livestreaming and recording of all public meetings and to display access information directly on NAIC’s website. This is not radical. http://petergould.com/PG-NAIC%20PROPOSED%20CHANGE-EC-MEETING%20ACCESS%20&%20RECORDINGS-2025-08-PROPOSAL%20&%20REDLINE%20AMENDMENT.pdf

Federal agencies routinely livestream and archive proceedings. State legislatures do the same. City councils do the same. Why is insurance regulation different?

Why This Matters for Annuities

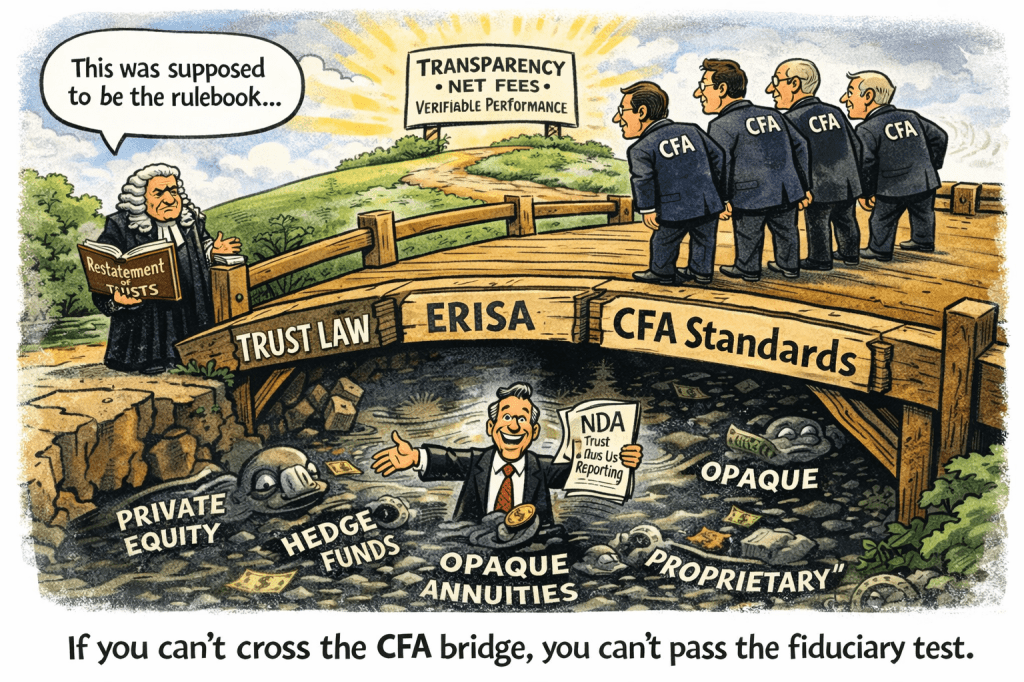

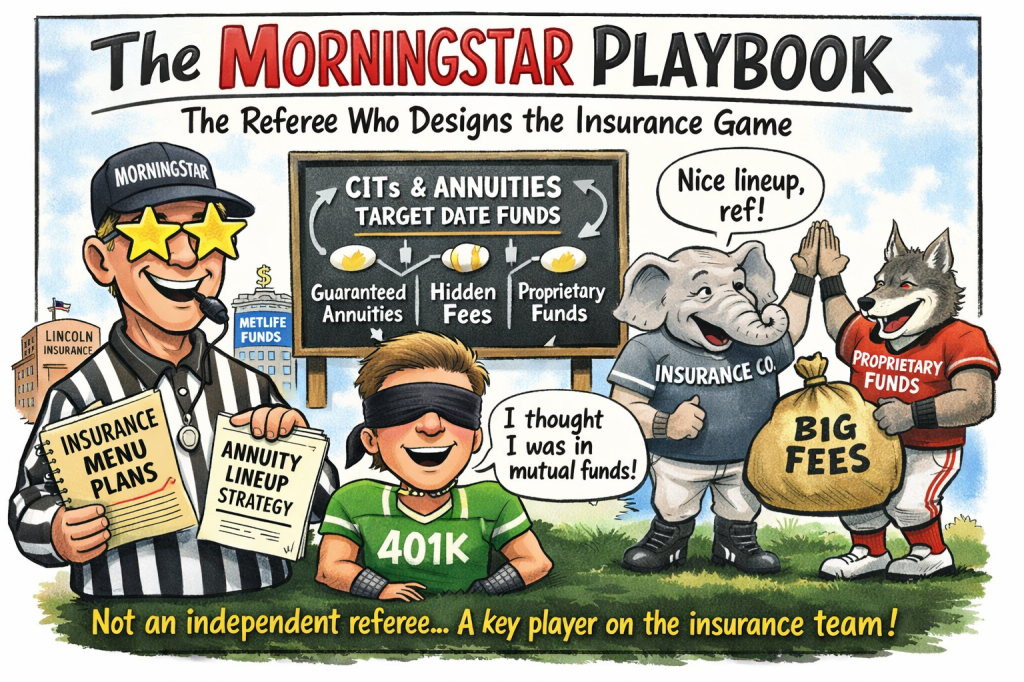

As argued previously in “Annuities: The ERISA Regulatory Hole No One Wants to Talk About,” retail annuities sit outside ERISA’s fiduciary framework and are governed almost entirely through state insurance regulation.

If that regulatory system is fragmented and opaque, then trillions of retirement dollars rest on a structure that is:

- Non-uniform

- Politically sensitive

- Industry-influenced

- Largely invisible to the public

Insurance companies operate through general accounts that are not benchmarked like mutual funds. Spread is undisclosed. Asset allocation is opaque. Private credit exposures are growing.

The one safeguard consumers have is solvency regulation.

If the solvency regulators operate behind velvet ropes, that safeguard weakens.

Fifty Regulators — But One Gatekeeper

The NAIC is not a federal agency. It is a standard-setting body composed of state regulators. It is deeply influential, yet structurally private.

That hybrid status creates ambiguity:

- Not fully public

- Not fully private

- Not fully accountable

- Not fully transparent

Gould’s proposal is modest. It does not change capital standards. It does not alter accounting rules. It does not weaken solvency requirements.

It simply says: If a meeting is public, let the public see it.

Transparency Is Not Anti-Insurance

Supporting this proposal is not anti-insurer. It is not anti-regulator.

It is pro-legitimacy.

In an era of:

- Private credit expansion inside life insurers

- Offshore reinsurance structures

- Bermuda-based balance sheet engineering

- Rising scrutiny of insurer asset risk

Public confidence in solvency regulation matters more than ever. If regulators are doing strong work, transparency strengthens them. If regulators are under pressure, transparency protects them.

Why I Support Peter Gould

Gould is not a hedge fund.

Not a trade association.

Not a plaintiff’s firm.

He is a retiree who depends on annuity contracts for income he cannot outlive.

He is asking for basic visibility into the regulatory body that determines whether his insurer remains solvent. That is not radical.

That is commonsense.

The Bigger Picture

Insurance regulation in America has always been decentralized. That is unlikely to change. But decentralization does not require opacity.

If the NAIC wants to reinforce its leadership position, it should embrace full transparency of public proceedings — livestreamed, archived, and freely accessible.

Because when trillions in retirement assets depend on solvency standards written in committee rooms, the public should not have to pay admission to watch.

Transparency is not a threat to insurance regulation. It is the only way to preserve trust in it.